The debate around Austrian taxation isn’t just academic, it’s deeply personal for those caught in the upper tax brackets. As one top 10% earner puts it bluntly: “Ein weiterer Aufstieg ist angesichts der völlig pervertierten Steuer- und Abgabensituation aus derzeitiger Sicht völlig unrealistisch.” (“Further career advancement is completely unrealistic given the completely perverted tax and contribution situation.”)

This sentiment resonates across Austria’s workforce, particularly among those who’ve achieved professional success only to find themselves questioning whether the system penalizes productivity rather than rewarding it.

The Austrian Tax Reality: Among Europe’s Highest Burdens

When a full-time single employee earning Austria’s average salary of €4,407 monthly faces a marginal tax rate of 58.25%, we’re not just discussing numbers, we’re examining a system that places Austria near the top of EU tax rankings. According to recent analysis, high earners in Austria pay among the highest taxes in the EU, surpassed only by Belgium and Italy.

The practical impact? Someone earning €75,000 annually in Austria keeps substantially less net income than their counterparts in Germany, Switzerland, or even neighboring Eastern European countries. This creates what economists call a “high effective marginal tax rate”, where each additional euro earned gets taxed at progressively higher rates, creating little financial incentive for additional effort.

The Psychology of Diminishing Returns

The research reveals a fascinating psychological shift occurring among successful Austrians. Many describe hitting an invisible ceiling where further effort yields diminishing lifestyle improvements. As one self-employed professional shared: “I calculated how much revenue I actually need. Since then I work about 15 hours per week at an hourly rate of €120 net. What was the result? Last year and this year I still made around €100,000 in revenue, but with much less stress than before.”

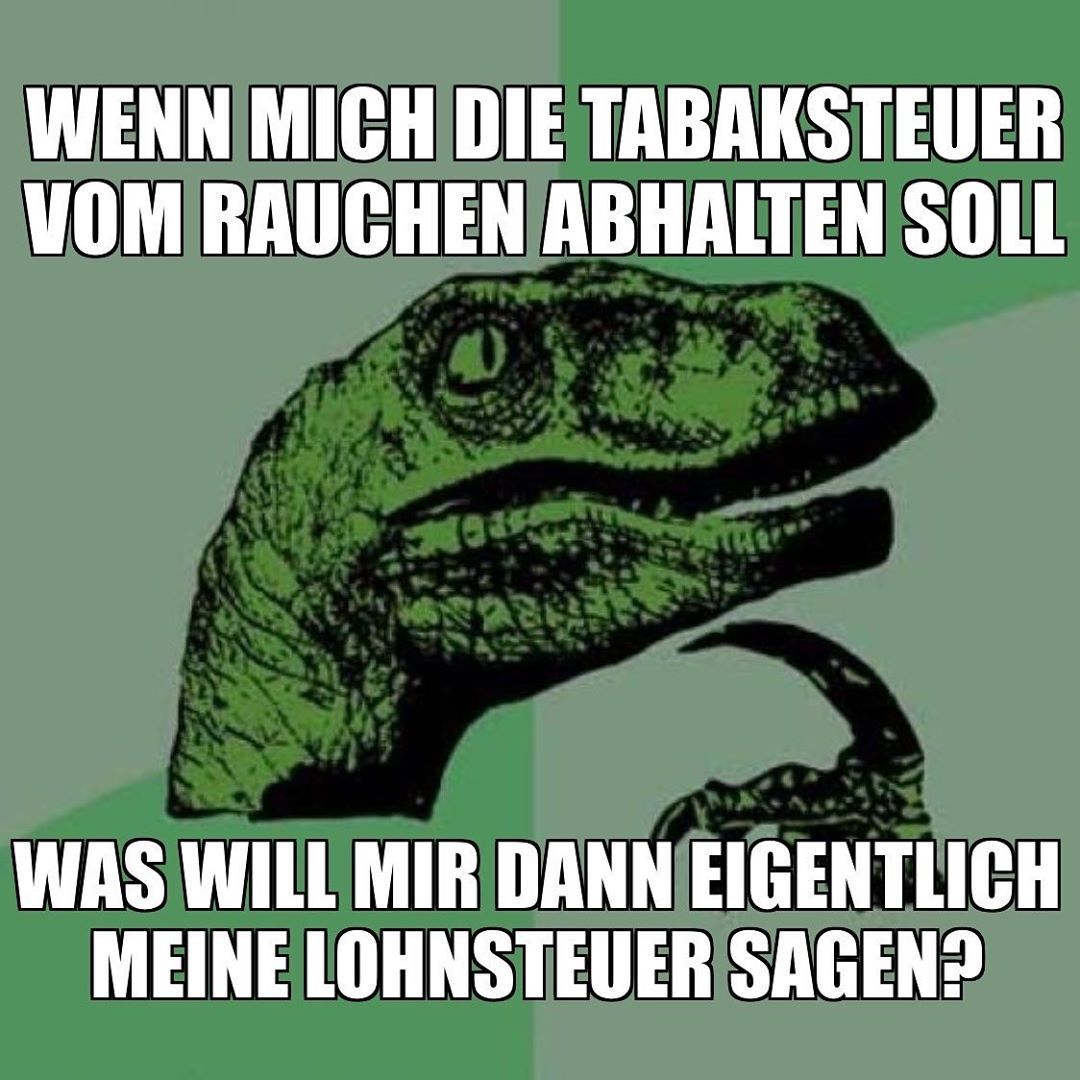

This isn’t isolated sentiment. In Austrian financial forums, the discussion frequently centers on the realization that “buying free time” with reduced work hours provides better value than pursuing additional taxable income. When you can “purchase” leisure time at a 1:1 ratio with your gross salary, but consumer goods require navigating 50% taxes plus 20% VAT, the rational choice becomes clear.

The Working Hours Paradox

Austria leads Europe in part-time work rates, and the tax structure provides a compelling explanation. As forum participants note: “Die geleisteten Arbeitsstunden gehen in Österreich seit Jahren zurück, gleichzeitig sind wir Europameister bei der Teilzeitquote.” (“The hours worked in Austria have been declining for years, meanwhile we’re European champions in part-time rates.”)

The mathematical reality is stark: working additional hours means entering progressively higher tax brackets where the government takes the majority share. This creates what behavioral economists call “tax-induced labor supply reductions”, in plain terms, people rationally choosing leisure over marginally profitable work.

Upcoming Changes: More Pain for Productive Workers

The situation appears poised to worsen. The new government program for 2025-2029 includes tax changes that will reduce overtime tax exemptions starting in 2026, effectively increasing taxation on extra work. This comes amid already intense frustration, with many Austrians expressing that “Anstatt Leistung zu belohnen wird man bestraft” (“Instead of rewarding achievement, you get punished”).

Even internationally, Austria’s approach serves as a cautionary tale. German politicians point to Austria as an example of what not to do, with Bavaria’s Economics Minister Hubert Aiwanger recently arguing that Austria’s inheritance tax model particularly harms high achievers, stating “Ich bin gegen die Erbschaftssteuer, die muss weg” (“I’m against inheritance tax, it has to go”).

The Bottom Line: Productivity Versus Taxation

The core issue isn’t merely high taxes, it’s the structure that disproportionately impacts those at their professional peak. When skilled professionals reach their 40s, traditionally peak earning years, many face a choice: continue climbing into near-confiscatory tax territory, or accept their current standard of living with significantly improved work-life balance.

International residents in Austria often experience this most acutely, having experienced different tax systems elsewhere. They report being stunned by how little additional take-home pay results from promotions or significant salary increases once taxes, social security contributions, and various levies accumulate.

The Path Forward: Strategic Responses

The silver lining? Austria’s system, while punishing for linear career progression, offers numerous legal optimization opportunities:

For employees: Maximizing pension contributions, utilizing the Pendlerpauschale (commuter allowance), strategically timing bonuses, and exploring company car options can significantly improve net position.

For self-employed: The situation differs dramatically, with far more flexibility in expense deduction, pension planning, and income timing. Many successful professionals transition to Einzelunternehmer or corporate structures once reaching certain income thresholds.

For all high earners: The key insight emerging from Austrian financial circles is rethinking the relationship between work and life satisfaction. Rather than chasing ever-higher gross salaries, the strategic approach involves optimizing the existing income through tax-efficient investments, proper retirement planning, and focusing on building wealth outside traditional employment income.

The uncomfortable truth for Austrian policymakers: when the tax system effectively penalizes productivity, the most ambitious and talented workers will either reduce their effort or take it elsewhere. As one commenter noted: “Bei diesen hohen Steuern bleibt ja nix mehr übrig außer auswandern oder Steuerhinterziehung” (“With these high taxes, nothing remains but emigration or tax evasion”).

Perhaps the most telling development is how many Austrians are quietly optimizing for lifestyle rather than career progression. They’ve discovered that in a high-tax environment, the best investment might just be reclaiming their time.