Austria’s pension landscape is about to experience its most significant shake-up in decades. On December 17, 2025, the federal government approved a comprehensive package that fundamentally restructures the Betriebliche Vorsorge (occupational pension) system, promising universal access and unprecedented flexibility. But beneath the sheen of reform lies a contentious debate that splits policymakers, industry leaders, and financial experts: does making pension savings more accessible create a genuine 401(k)-style opportunity, or does it simply gut the system’s core purpose?

The 2027 Overhaul: What Actually Changes

The centerpiece of the reform is the Generalpensionskassenvertrag, a universal pension fund contract that will, for the first time, grant every employee access to occupational pension schemes regardless of whether their employer voluntarily offers one. Currently, only about 25% of Austrian workers can participate in Betriebliche Vorsorge, leaving the vast majority dependent on the state pension and private savings. This changes in 2027.

The new framework introduces three critical mechanisms:

First, employees will be able to transfer their Abfertigung Neu (severance pay) balances into a pension fund free of charge. This represents a fundamental shift from a lump-sum entitlement at employment termination to a long-term retirement asset. For a mid-career professional with €30,000-€50,000 in accumulated severance, this transfer could substantially boost their retirement capital.

Second, the government is examining a “Herausnahmemöglichkeit bei Pensionsantritt”, the option to withdraw accumulated funds as a lump sum upon retirement rather than converting them into an annuity. This mirrors the flexibility of American 401(k) plans, where participants can choose between lump-sum distributions or periodic payments.

Third, hardship provisions will allow limited, controlled access to pension assets during periods of long-term unemployment or serious illness. While this introduces a safety net, it also raises questions about whether premature withdrawals will deplete retirement funds when they’re needed most.

The Industry’s Alarm Bell: “Mittelfristig ruinieren”

The most vocal critic of these changes is Andreas Zakostelsky, chairman of the Austrian Chamber of Commerce’s pension and provident fund association. His condemnation is blunt: allowing unrestricted access to Abfertigung Neu funds will “ruin the system in the medium term.” His core argument is philosophical rather than technical: “Where remains the savings purpose if money can be withdrawn or transferred at any time?”

This criticism strikes at the heart of Austria’s pension culture, which traditionally emphasizes mandatory, illiquid savings to ensure basic retirement security. The proposed flexibility, Zakostelsky argues, transforms a vorsorgende Einrichtung (provident institution) into a glorified savings account with tax benefits, one that individuals might raid for immediate needs, leaving them vulnerable in old age.

The government’s counterargument, articulated by NEOS leader Beate Meinl-Reisinger, frames this as a “milestone” for personal freedom. Why should pension fund managers dictate how individuals handle their own money? If someone wants to invest their severance in a world equity ETF rather than a conservative pension fund, shouldn’t that be their prerogative?

Comparing Apples and Oranges: Betriebliche Vorsorge vs. 401(k)

The 401(k) comparison is tempting but requires nuance. American 401(k) plans are employer-sponsored, voluntary, and feature immediate vesting of employee contributions. Austria’s reformed system differs in crucial ways:

Tax treatment: While 401(k) contributions are tax-deferred, Austrian occupational pension contributions are typically funded via the Abfertigung Neu, which is already a mandatory employer contribution. The tax advantage comes at payout, where benefits may receive favorable treatment compared to regular income.

Employer role: In the U.S., employers often match employee contributions, creating powerful incentives to participate. Austria’s Generalpensionskassenvertrag removes the employer gatekeeper but also eliminates the possibility of employer matching, which could limit contribution levels.

Investment control: The proposed reforms suggest greater individual investment choice, potentially allowing ETF investments as some commentators desire. However, pension funds will likely impose default conservative strategies, meaning true investment freedom remains uncertain.

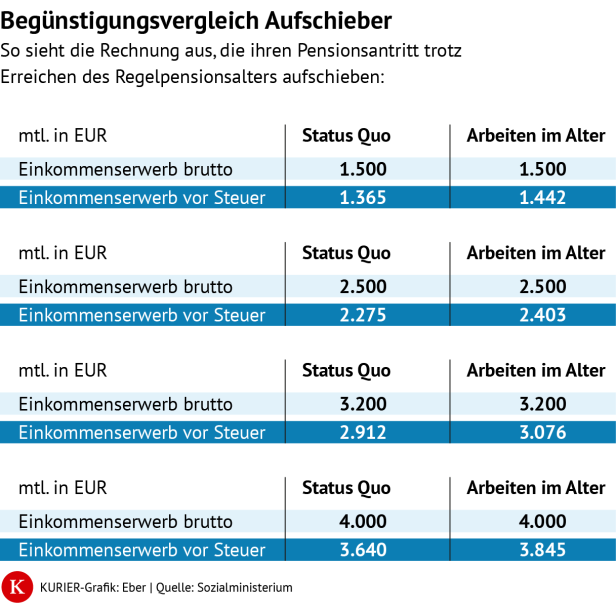

The €15,000 annual tax-free allowance for pensioners’ additional income, while not directly part of the occupational pension reform, creates a complementary incentive structure. A retiree could theoretically withdraw €15,000 annually from their pension fund without tax liability, mimicking 401(k) distribution strategies.

Who Wins, Who Loses

The distributional effects reveal the reform’s political calculus. The tax-free allowance benefits lower and middle-income pensioners disproportionately compared to the originally proposed flat tax of 25%, which would have favored high earners. This shift explains why the SPÖ and pensioner associations support the change while the ÖVP-aligned Seniorenbund criticizes the delayed implementation.

For employees, universal access eliminates a major inequality. A 35-year-old graphic designer at a small startup gains the same occupational pension opportunities as a bank employee at a large corporation. The ability to transfer Abfertigung Neu balances means younger workers can compound these funds for 30+ years rather than receiving a modest lump sum when changing jobs.

However, the self-employed remain in a gray area. While the €15,000 tax-free allowance applies to them, the occupational pension reforms focus on employees. This perpetuates a two-tier system where traditional employees receive multiple layers of retirement support while freelancers must navigate private Vorsorge alone.

The Timing Problem: Why 2027?

The government’s decision to postpone implementation until 2027, despite initial promises of 2026, has drawn fire. The official explanation cites the need for detailed legislative work, but the political subtext is clear: this gives coalition partners time to negotiate implementation details and allows the pension industry to adapt its systems.

For workers nearing retirement, this delay is consequential. Someone retiring in 2026 just misses the enhanced flexibility, while their colleague retiring in 2028 can withdraw a lump sum. This arbitrary cutoff creates a sense of intergenerational unfairness.

Practical Implications: What Should You Do?

If you’re currently employed in Austria, the immediate action is to review your Abfertigung Neu balance through your employer’s payroll records. Understanding whether you have €5,000 or €50,000 accumulated will shape your strategy once transfers become possible in 2027.

For those already participating in Betriebliche Vorsorge, the reforms likely mean more investment options and potentially lower fees due to increased competition among pension funds. The universal access mandate should pressure providers to improve their offerings.

Critically, don’t view the potential lump-sum withdrawal as “free money.” Financial planners warn that a €30,000 withdrawal at age 65 could translate to €150-200 less monthly income for life, depending on annuity rates. The temptation to fund a retirement dream, renovating a vacation home in Carinthia, for instance, must be weighed against decades of reduced income.

The Verdict: Opportunity or Experiment?

Austria’s Betriebliche Vorsorge reforms create something genuinely new: a universal, portable, partially flexible occupational pension system that borrows from 401(k) principles while retaining Austria’s collective risk-sharing ethos. For the 75% of workers previously excluded, this is undeniably an opportunity.

Yet the experiment lies in the balance between flexibility and security. If too many individuals withdraw funds prematurely, whether for hardship, job changes, or retirement lump sums, the system’s actuarical foundations could weaken, leading to higher fees or reduced benefits for those who maintain their savings. The government’s challenge is implementing controls that prevent abuse without creating the bureaucratic nightmare the reforms aim to eliminate.

The reforms don’t transform Austria into a 401(k) culture overnight. But they do create a hybrid system that, if executed carefully, could offer the best of both worlds: universal coverage with individual autonomy. Whether that happens depends on the legislative details worked out in 2026, and on Austrian savers resisting the siren call of immediate gratification when their retirement security is at stake.

For now, the smart move is to educate yourself, monitor the legislative process, and prepare to make informed decisions when 2027 arrives. Your future retired self will thank you for treating this new flexibility as a tool for strategic planning, not an ATM for short-term needs.