Austrian politicians have discovered a brilliant solution to budget problems: redefine success. While Finance Minister Markus Marterbauer (SPÖ) calls the latest inflation figures “sensational”, ÖVP Finance Secretary Barbara Eibinger-Miedl insists Austria suffers from a spending problem, not a revenue problem. The cognitive dissonance would be amusing if it weren’t so expensive for taxpayers, especially the ones who haven’t voted yet.

The phrase “lifestyle inflation” typically describes individuals who spend more as they earn more, upgrading from Spar to Billa, from public transport to leased Audis. But the metaphor fits Austria’s state finances disturbingly well. The government expands expenditures while delivering diminishing returns to citizens, particularly younger generations who watch their future security evaporate in real-time.

The 30% Price Hike That Officialdom Ignores

Let’s start with the numbers that actually matter to people filling their shopping carts. Austrian prices have risen nearly 30% since 2020, significantly outpacing the Eurozone’s 23.5% increase. When confronted with this gap on ZiB 2, Eibinger-Miedl blamed “special challenges” like Russian gas dependency and wage increases. The explanation feels less than complete when you’re staring at a €4.50 liter of milk.

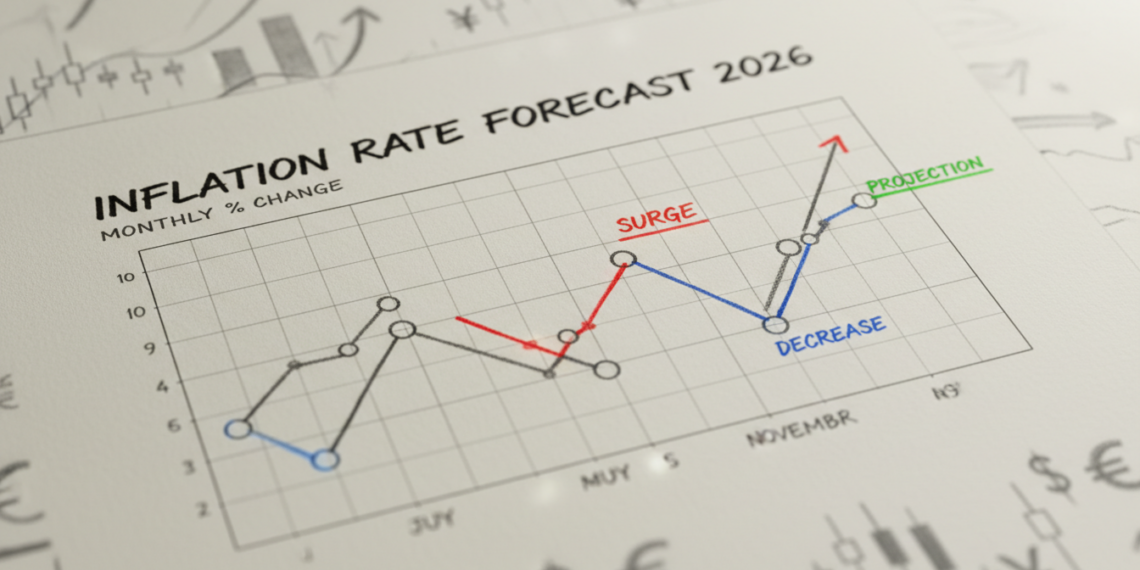

The government’s response? Celebrating that inflation “slowed” to 2% in January 2026 while ignoring that prices remain permanently elevated. As one observer noted during the broadcast, nobody is actually being “relieved”, prices simply continue climbing at a slightly less terrifying rate. This is like congratulating yourself for slowing the car from 150 km/h to 130 km/h while still heading straight for a wall.

The disconnect between official metrics and lived reality fuels distorted official cost-of-living benchmarks versus real household pressures. When Statistik Austria reports cooling inflation, but your Billa receipt shows 25% higher grocery costs and your Nebenkosten (ancillary costs) for an Altbau (old building) apartment spiked 40%, the numbers feel like fiction.

The Spending Problem That Isn’t

Eibinger-Miedl’s mantra, “Austria has a spending problem, not a revenue problem”, has become gospel in ÖVP circles. The claim conveniently ignores that long-term budget projections show the deficit rising to 7.4% by 2026 and state debt ballooning from 82% to 146% of GDP. That’s not discipline, it’s denial.

The Krone Zeitung recently exposed how the government claims credit for a €3.7 billion budget improvement that experts attribute to external factors, not policy decisions. The “unexpected billions” reflect accounting maneuvers and favorable economic tailwinds, not fiscal responsibility. Meanwhile, the structural deficit remains catastrophic.

This pattern reveals a deeper pathology: Austrian governments of all stripes expand the state’s footprint during good times while refusing to contract during crises. The result is what economists call “state lifestyle inflation”, permanent spending increases that outpace economic growth and demographic realities.

The Wealth Tax Debate That Exposes Everything

The inheritance tax (Erbschaftssteuer) controversy perfectly illustrates the generational divide. The SPÖ pushes for a referendum on wealth and inheritance taxes, while the ÖVP blocks it, citing coalition agreements. Eibinger-Miedl dismisses the idea entirely, claiming Austria needs spending cuts, not new revenue.

Critics point out a fundamental inequity: top earners pay nearly 50% income tax (Einkommensteuer) on salaries, while capital gains face only 27.5% KESt (capital gains tax). Most wealth transfers through inheritance, meaning heirs receive fortunes they didn’t earn while paying lower effective rates than workers. As one financial analyst calculated, a €1 million salary incurs ~50% tax, while €1 million in corporate distributions costs 27.5% KESt plus corporate tax, still significantly less than pure labor income.

The ÖVP’s resistance to even discussing the issue reveals whose interests it prioritizes. One commenter noted that exempting the first €2 million from inheritance tax would exclude 90% of Austrians entirely. The debate isn’t about middle-class families losing their homes, it’s about whether the ultra-wealthy should contribute more to a system that protects their assets.

Generation Z: Politically Interested, Politically Abandoned

The Ö3 Youth Study 2025 surveyed 28,000 young Austrians aged 16-25, revealing a stark disconnect. While 77% describe themselves as politically interested, only 22% feel represented by politicians. A staggering 79% distrust political actors.

This mistrust isn’t anti-democratic, it’s anti-hypocrisy. Young people watch political decisions that ignore their reality. Pensions (Renten) and future security dominate their concerns, yet policy consistently favors current retirees at their expense. The unspoken contract, that each generation supports the previous one in exchange for future support, feels broken.

The study shows young Austrians crave stability, clear rules, and reliable frameworks. Instead, they get budget deficits they’ll inherit, climate inaction they’ll pay for, and housing markets they’ve been priced out of. The state’s “lifestyle inflation”, spending on today’s voters while ignoring tomorrow’s, breeds justified cynicism.

The Pension Time Bomb and Silent Exodus

This generational unfairness manifests most clearly in Austria’s pension system. The research shows eroding trust in state-provided financial security as three out of four Austrians now believe their state pension won’t suffice. Younger workers increasingly treat social insurance contributions as a sunk cost rather than an investment.

The math explains why. Austria’s pension system relies on current workers funding current retirees. As the population ages and birth rates decline, the ratio collapses. Yet reforms remain taboo, with politicians protecting today’s pensioners, their core voter base, while making vague promises about future fixes they won’t be around to implement.

This creates a silent exodus where middle-class Austrians build private savings as a hedge against state failure. They’re not abandoning the pension system out of greed, but survival instinct. The state’s lifestyle inflation, promising benefits it mathematically cannot deliver, forces citizens to opt out where they can.

Housing: The Ultimate Example of State Failure

Austrian housing policy demonstrates lifestyle inflation’s real-world damage. The state spends billions on housing subsidies, Wohnbauförderung (housing construction subsidies), and social housing, yet Vienna’s market remains brutally unaffordable for young buyers. A €300,000 apartment on a €2,650 net income requires savings and subsidies that most can’t access, as detailed in unsustainable homeownership incentives despite stagnant incomes.

The disconnect stems from policies designed for post-war scarcity, not today’s asset inflation. While the state maintains elaborate subsidy systems, it fails to address supply constraints, zoning restrictions, and the fundamental mismatch between wages and property values. Young Austrians don’t need more complex programs, they need the state to stop inflating its role and start enabling market solutions.

The Inflation Illusion and Personal Financial Reality

Government spending directly feeds inflation through fiscal stimulus. As Rathaus Nachrichten explains, rising state expenditures boost growth but amplify inflationary pressures at capacity limits. Austrians experience this as personal financial strain versus official inflation reporting that feels fictional.

The official 2% inflation figure masks sector-specific explosions. Energy, housing, and food, essentials for young families, have risen far faster. Meanwhile, the state’s response involves more spending on “relief” measures that often just redistribute rather than reduce costs. It’s like treating a fever by adding blankets.

This creates a vicious cycle: spending drives inflation, which justifies more spending, which drives more inflation. Citizens see their purchasing power erode while the state congratulates itself for “managing” the problem. The lifestyle inflation analogy holds, just as personal lifestyle inflation leaves individuals broke, state lifestyle inflation leaves governments insolvent and citizens poorer.

What Austrians Are Actually Saving For

Against this backdrop, Austrian savings behavior reveals desperation disguised as prudence. Research on how Austrians are prioritizing financial survival over long-term wealth building shows people aren’t saving for retirement dreams, but for basic security.

The portfolio allocations reflect fear, not ambition. Cash holdings remain high despite inflation. Real estate is pursued not as an investment but as inflation protection. And younger savers increasingly look abroad, distrusting Austrian financial institutions and state promises. This capital flight, of money and confidence, represents a quiet vote of no confidence in the state’s fiscal trajectory.

The Path Forward: From Lifestyle Inflation to Financial Fitness

Fixing Austrian state lifestyle inflation requires what personal finance experts recommend for individuals: brutal honesty about income and expenses, prioritization of needs over wants, and long-term planning over short-term gratification.

Specifically, Austria needs:

1. Transparent accounting that distinguishes structural from cyclical spending

2. Intergenerational impact assessments for all major fiscal decisions

3. Automatic stabilizers that reduce spending when growth exceeds targets

4. Constitutional debt brakes with real enforcement mechanisms

5. Tax reform that reduces labor taxation while addressing wealth concentration

The Ö3 Youth Study shows young Austrians aren’t asking for handouts, they want fairness, stability, and honesty. They understand that the gap between public financial aspirations and economic reality under current state policies makes traditional planning impossible.

Conclusion: The Bill Is Coming Due

Austrian state lifestyle inflation persists because the costs are diffused across time and generations while benefits concentrate among today’s organized interests. Politicians face no immediate penalty for promising more than the state can deliver, especially when they can claim credit for “managing” crises they helped create.

But the bill is coming due. The 2026 budget projections aren’t theoretical, they’re promises that will either be broken or paid through higher taxes, reduced services, or inflationary money printing. Young Austrians already sense this, which explains their political distrust and financial anxiety.

The solution isn’t complicated, but it is politically painful: stop treating state spending as a lifestyle upgrade and start treating it as the constrained resource it is. That means saying no to organized interests, yes to transparency, and maybe, just maybe, letting citizens keep enough of their income to build their own security rather than funding a state that can’t deliver it.

Until then, Austria’s government will continue its luxury spending spree, leaving younger generations to figure out how to survive on what’s left. And what’s left feels smaller every month, no matter what the official inflation figures say.