Magali and Emmanuel, both 50, stand in a Cergy shopping center and deliver a verdict that would have shocked their parents: “We live worse than they did, even though we earn more.” Emmanuel, a RATP employee, points out the obvious proof, his parents owned a second home that served as a family retreat. He and Magali, a nurse, can barely afford their primary residence in the Yvelines. This isn’t a unique complaint. Across France, a quiet consensus is forming that the generational contract has been broken.

The numbers back up this feeling. According to Eurostat, France’s GDP per capita has fallen below the EU average for three consecutive years. We’re not just talking about a statistical blip, this puts French living standards behind Ireland, the Netherlands, and Belgium, while Poland and the Czech Republic are closing the gap fast. France’s declining wealth relative to Europe isn’t some abstract economic indicator, it’s the reason why middle-class professionals in Paris can’t afford what their parents managed on single incomes.

The Housing Trap: When “Chez Soi” Becomes a Luxury

The most visible symbol of this decline is housing. Emmanuel’s parents bought their second home decades ago when property prices tracked incomes. Today, the equation has shattered. In Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a modest 42m² two-room apartment now costs €227,700, if you can find one. In Bordeaux, a 23m² studio commands €199,000. These aren’t Paris intra-muros prices, they’re suburban realities that make the French dream of property ownership feel like a bad joke.

This is where buying vs renting in France and outdated generational advice becomes a flashpoint. Your parents’ generation will still tell you that renting is “jeter de l’argent par les fenêtres” (throwing money out the window). But they’re calculating from a world where a fonctionnaire (civil servant) could buy a house in the suburbs on one salary. Today, a couple of infirmiers (nurses) with stable jobs struggles to qualify for a prêt immobilier (mortgage) that would cover even a modest property within commuting distance of Paris.

The math is brutal. While salaries nominally increased, housing costs in major French cities have multiplied by factors of 5 to 10 since the 1980s. The result? Homeownership rates among 30-40 year-olds have stagnated while the age of first-time buyers keeps climbing. You’re not just paying more for the same roof, you’re getting less space, longer commute times, and a mortgage that chains you to your job for 25 years.

The Social Contribution Vacuum: Where Did Half Your Salary Go?

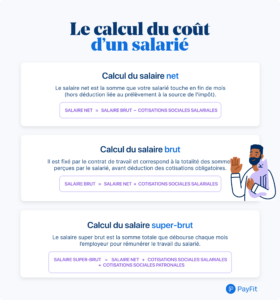

Walk into any French workplace and you’ll hear the same complaint: “On nous prend la moitié de notre salaire pour les retraités” (They take half our salary for the retirees). It’s hyperbole, but not by much. A 1973 pay stub shows total deductions at 8.7% of gross pay. Today, that figure hovers around 45-50% when you combine cotisations sociales (social contributions), impôt sur le revenu (income tax), and other levies.

This isn’t just about high taxes, it’s about what you get in return. The deal used to be simple: pay your cotisations now, enjoy a generous retraite (pension) later. But pension system insecurity and generational anxiety has destroyed that trust. A January 2026 survey showed 87% of non-retired French fear for retirement’s future, and 80% worry about their own pension. You’re paying for a system that may not exist when you need it.

The French social model, once the envy of Europe, now feels like a Ponzi scheme to younger workers. Your cotisations fund current retirees who enjoyed job security, defined-benefit pensions, and property appreciation. You get precarious contracts, points-based retirement, and a housing market that’s already peaked. The generational transfer isn’t just unfair, it’s unsustainable.

The Purchasing Power Illusion: Why Statistics Lie to You

Here’s where it gets weird. Official data shows French purchasing power increased in 2025. Inflation dropped to 0.3% in January 2026. The revenu disponible brut (gross disposable income) of households rose. By the numbers, you should feel richer.

But you don’t. And you’re not imagining it.

The disconnect lies in what economists call “perceived inflation.” While headline numbers look tame, prices in non-negotiable categories, food, services, insurance, keep climbing. The poste sensible (sensitive budget items) in your account don’t follow official statistics. Your car insurance jumps 15%. The cantine (workplace cafeteria) increases prices. The €5 baguette is now €6. These micro-pressures accumulate while your salary stays flat.

This explains why 77% of French believe “le travail ne paie plus” (work no longer pays). According to Elabe polling, only 23% think employment actually improves financial situations. The rest see their efforts swallowed by a system where gains are statistical but losses are painfully real.

The Middle Class: “Les Dindons de l’Histoire”

Martial You, economic editorialist at RTL, calls the middle class “les dindons de l’historie” (the turkeys of history). They’re the good students who did everything right, studied, worked stable jobs, saved, and find themselves déclassés (downgraded) anyway.

The middle-class contract in France rested on four pillars: work, property, education, and social mobility. All four are cracking. Work no longer guarantees security. Property is out of reach. Education credentials have inflated while value has dropped. And the ascenseur social (social elevator) is jammed between floors.

This is why Emmanuel and Magali’s story matters. They’re not struggling because they failed. They have stable public-sector jobs, a house in the Yvelines, three kids. By their parents’ standards, they’ve succeeded. Yet they feel precarious, unable to replicate their parents’ lifestyle despite earning more in absolute terms.

The Investment Dead Ends: Where Can You Put Your Money?

Faced with stagnant wages and rising costs, the logical move is to invest. But French investment options have their own traps. SCPI crisis and real estate liquidity risks show how even “safe” real estate investments turned into liquidity nightmares. Shares in property investment trusts that promised 4-5% returns became impossible to sell when everyone headed for the exit.

For those trying to escape the rat race early, Barista FIRE and part-time work challenges in France reveal another harsh truth: part-time work that covers living expenses barely exists. The French labor market is binary, full-time CDI (permanent contract) or precarious CDD (fixed-term contracts). There’s no middle ground where you can work 20 hours a week and still afford rent.

Even traditional safe havens have failed. Gold’s recent 30% crash shattered its reputation as portfolio insurance. The PEA (Plan d’Épargne en Actions, the French stock savings plan) offers tax advantages but can’t compensate for a market that feels increasingly disconnected from economic reality.

The Broken Generational Contract: What Comes Next?

The paradox isn’t just economic, it’s psychological. Your parents’ generation measured success in stability: a job for life, a paid-off house, a retraite dorée (golden retirement). You measure success in flexibility, experiences, and resilience. But that’s partly because stability is no longer on offer.

This shift explains why 51% of French now prioritize budget reduction over working more to improve their situation. When extra work yields marginal gains after taxes and social charges, cutting expenses becomes the rational choice. It’s also why 31% would consider moving to a cheaper region, even if it means leaving family and established networks.

The French model assumed a continuous upward trajectory. Each generation would live better than the last. That assumption has collapsed. Today, the question isn’t whether you’ll live better than your parents, but whether you can maintain their standard at all.

The Hard Truth: Adaptation Over Aspiration

What does this mean practically? First, stop measuring yourself against your parents’ timeline. Their financial advice, “buy property as soon as possible”, “stay in one job”, “count on the retraite by rights”, is obsolete. Buying vs renting in France and outdated generational advice needs to be filtered through current reality.

Second, understand that the French social model requires active management. You can’t passively contribute and expect returns. Track your cotisations, understand your pension points, and treat the system as a supplement, not a foundation.

Third, diversify beyond France. With French GDP per capita lagging the EU, tying your entire financial future to the Hexagon is concentration risk. European ETFs, remote work for international companies, and geographic arbitrage aren’t just options, they’re necessities.

Finally, accept that the middle-class script has been rewritten. The goal isn’t replication of your parents’ lifestyle, but designing a sustainable one for current conditions. That might mean renting in a city center instead of buying in the suburbs. It might mean a remote job for a US company paying in dollars. It might mean skipping the expensive French education system for international alternatives.

Magali and Emmanuel’s parents didn’t face these choices. They followed a clear path and were rewarded. Today, the path is gone, replaced by a maze where each turn demands calculation. You’re earning more than your parents did, yes. But you’re also paying more, for housing, for security, for the privilege of living in a France that no longer guarantees what it once promised.

The paradox isn’t in your head. It’s in the numbers, the policies, and the broken promises of a system that hasn’t adapted to new realities. Recognizing that is the first step toward building something that actually works, for this generation, not the last.