Klaus Regling has spent decades pulling economies back from the brink. As managing director of the European Stability Mechanism, he steered eurozone bailouts and rewired fiscal frameworks. Now, the 75-year-old economist delivers an unsettling verdict on his own country: German households are heading for a sustained decline in real disposable income, and the political system may be too paralyzed to stop it.

Regling’s warning, first reported by Handelsblatt and amplified across German media, lands like a cold shower on a economy already grappling with stagnation. “Even if the economy recovers somewhat, the real disposable income of Germans will likely decline in the future”, Regling stated flatly. For the first time in the Federal Republic’s history, he adds, the core promise that children will live better than their parents is probably no longer tenable.

The Numbers Behind the Warning

Germany’s economic engine hasn’t just sputtered, it’s been idling for three years. While politicians debate Klimaschutz and Verteidigungsfähigkeit, the underlying metrics tell a sobering story. Regling points to a perfect storm: demographic aging, underinvestment in infrastructure, ballooning social security costs, and intensifying global competition from China and the U.S.

The Tagesspiegel coverage highlights his core argument: a growing share of Germany’s economic output will be consumed by defense “zwei-Drittel-Mehrheit” scenarios. Defense spending, climate adaptation, and pension obligations are crowding out consumption. The next generation will simply have less to spend.

This isn’t abstract macroeconomics. Many working professionals already feel the squeeze. One software engineer in Munich noted his net salary had risen 75% over his career, yet his living standard hadn’t improved at all. The gains vanished into higher Abgaben, housing costs, and inflation. Another resident recalled struggling to afford an apartment on €960 monthly when the minimum wage was €8.50. After retraining, his €1,800 net income still barely covers basic expenses in today’s market.

Why Reforms Keep Failing

Regling doesn’t mince words about the solution: Germany needs “the most comprehensive reform package in its history”, backed by a cross-party Großer Kompromiss. The challenge? Germans have spent years rejecting exactly that.

The Reddit discussion around Regling’s warning reveals a population deeply skeptical of change. Many express frustration that every reform attempt, whether Rente mit 67, Agenda 2010, or Hartz IV, gets watered down or politically weaponized. The consensus among commenters: the political will doesn’t exist because the electorate doesn’t want it.

This creates a feedback loop. Politicians propose modest adjustments, slightly higher retirement ages, limited Ehegattensplitting reforms, or cautious labor market changes, and face immediate backlash. The reforms get diluted, the underlying problems worsen, and public trust erodes further. As one observer put it: “We want innovation, but everything must be perfectly regulated. We want industry, but we can’t cut down pine forests. We want a strong social state and low taxes.”

Regling’s specific proposals read like a political minefield:

Work longer: Align retirement age with increased life expectancy

Work more: Increase average working hours, currently far below OECD peers

Abolish Ehegattensplitting: The tax benefit for married couples creates “false incentives”

Cut holidays: Consider eliminating some public holidays

Limit pension indexation: Switch to inflation-only adjustments, breaking the link to wage growth

Higher patient contributions: Introduce co-payments in healthcare and eliminate sick pay for the first day off

Each measure would spark massive protests. Yet Regling insists citizens will accept painful reforms if they believe the burden is distributed fairly. That means higher taxes on wealth and inheritances, not just squeezing workers.

The Japan Parallel

Several commentators see Germany’s trajectory mirroring Japan’s: a “tough but steady decline over several decades.” The comparison stings because Japan’s stagnation stemmed from similar dynamics, aging population, resistance to immigration, rigid labor markets, and political gridlock.

The difference? Japan started its slide from a higher baseline and maintained social cohesion. Germany faces these challenges while simultaneously managing Energiewende, digitalization gaps, and geopolitical pressures on its export-dependent model.

Regling specifically warns that Germany’s AAA rating and low borrowing costs aren’t eternal. “Special assets” (Sondervermögen) for defense or climate won’t remain viable if debt levels trigger rating downgrades. The market professionals, he notes, aren’t pricing in serious German risk, yet. But that can change fast when demographic math collides with fiscal reality.

What Actually Helps Individuals

While waiting for a political Durchbruch that may never come, residents can take concrete steps:

- Diversify income streams: Relying solely on Arbeitskraft (labor income) becomes riskier as wage growth lags. Side businesses, freelance work, or investment income provide buffers.

- Maximize tax-advantaged savings: Use every available Vorsorgeaufwendungen deduction. The Riester-Rente and BAV (company pension) remain worthwhile despite their limitations, simply because marginal tax rates bite so hard at relatively modest incomes.

- Internationalize assets: Germany’s problems are somewhat insulated. ETFs holding global equities, foreign real estate, or even simple currency diversification can hedge against domestic stagnation.

- Skill relentlessly: The commenter who tripled his salary through retraining proves human capital remains the best investment. But choose fields with global demand, not just German market needs.

- Plan for longer working lives: Whether the retirement age officially rises or not, personal financial math now requires working into the late 60s for most non-wealthy households.

The Political Reality Check

Regling’s call for a “grand bargain” implies something German politics currently makes nearly impossible: trust. The Koalition would need to present a unified, decades-long reform plan where everyone sacrifices something. Wealthy accept higher Erbschaftsteuer. Workers accept longer hours. Pensioners accept slower increases. Environmentalists accept infrastructure spending. Fiscal hawks accept strategic debt.

The comments suggest deep cynicism. Many believe even perfect politicians would fail because voters want contradictory things: strong social safety nets without high taxes, industry without environmental impact, security without military spending. This Wunschdenken (wishful thinking) fuels populist alternatives that promise easy answers.

Regling acknowledges his proposals are “politically delicate.” That’s diplomatic speak for “electoral suicide.” Yet he maintains citizens will support difficult changes if they see fairness. The problem is that fairness itself has become a partisan battleground.

Bottom Line: Prepare for Lower Expectations

The uncomfortable truth in Regling’s warning is that decline is already here, just unevenly distributed. Real wages haven’t recovered to pre-pandemic levels for many. The Kaufkraft (purchasing power) erosion feels more severe in prosperous cities where housing costs devour income growth.

Without the comprehensive reforms Regling outlines, unlikely before a genuine crisis, households must adjust personally. That means saving more aggressively, spending more deliberately, and abandoning the assumption that each generation naturally outperforms the last.

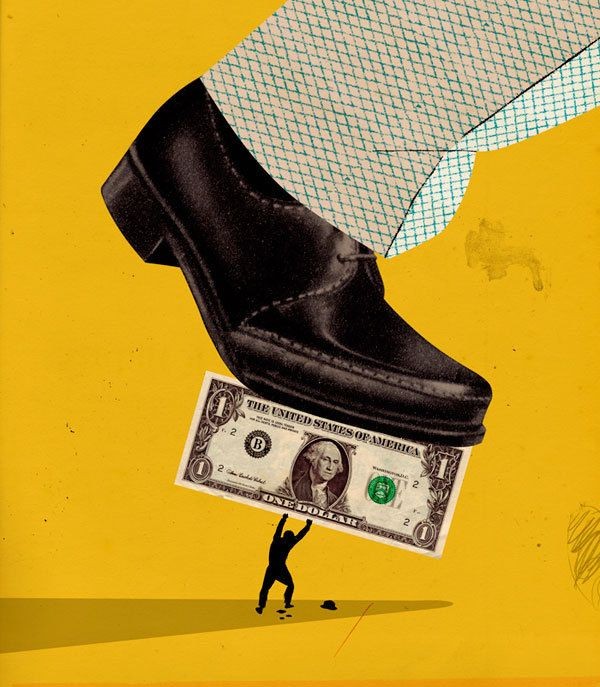

The 20-euro bill folding into a bird and flying away isn’t just symbolic. It represents a broader flight of economic vitality that German policy, for all its technical competence, hasn’t figured out how to anchor. Regling’s prescription is bitter medicine. The question isn’t whether it would work, but whether Germany will take it before the illness becomes terminal.

For now, the smart money is on individual adaptation rather than systemic salvation. The Wirtschaftswunder isn’t coming back, not because Germany lacks talent or resources, but because its political and social immune system rejects the treatment.