Why Do So Few Germans Invest? Breaking Down the Barriers

Germany sits on a mountain of cash, over €10 trillion in private wealth, growing at record pace, yet behaves like a nervous pensioner stuffing money under the mattress. While Americans embrace stock ownership (62% of adults), barely 17% of Germans hold equities, ETFs, or funds. The rest watch their purchasing power evaporate in savings accounts earning 0.5% while inflation runs at 3-4%. This isn’t just risk aversion, it’s a national pathology rooted in generational trauma, institutional failure, and a cultural distrust of markets so deep that "Aktien" still triggers memories of family ruin.

The Ghost of Telekom Past

Ask any German over 45 why they avoid stocks, and you’ll hear the same story: "Opa Alfred lost 5,000 DM on Telekom in 2000." The 1996 Telekom IPO was supposed to democratize investing, turning citizens into shareholders. Instead, it became a generational wound. The stock peaked at €100, collapsed below €10, and never recovered. For millions, this wasn’t a market correction, it was proof that Aktien sind Teufelszeug (stocks are the devil’s work).

This trauma gets passed down like a cursed family heirloom. Parents who watched savings vanish now warn their children: "Never touch that casino." The irony? They weren’t wrong to be suspicious, but they blamed the wrong villain. As one financial analyst noted, it wasn’t the stock market that burned them, it was their friendly Sparkasse advisor pushing overpriced, commission-heavy products while calling it "sicher" (safe). The advisor got his bonus. Opa got a lifetime of skepticism.

The pattern repeated with Swiss Franc loans in the 90s (where homeowners lost everything on currency bets sold as "clever") and again with Wirecard, where even politicians vouched for a DAX company that turned out to be fraudulent. Each scandal reinforced the same lesson: the system is rigged, and you’re the mark.

The German Savings Paradox

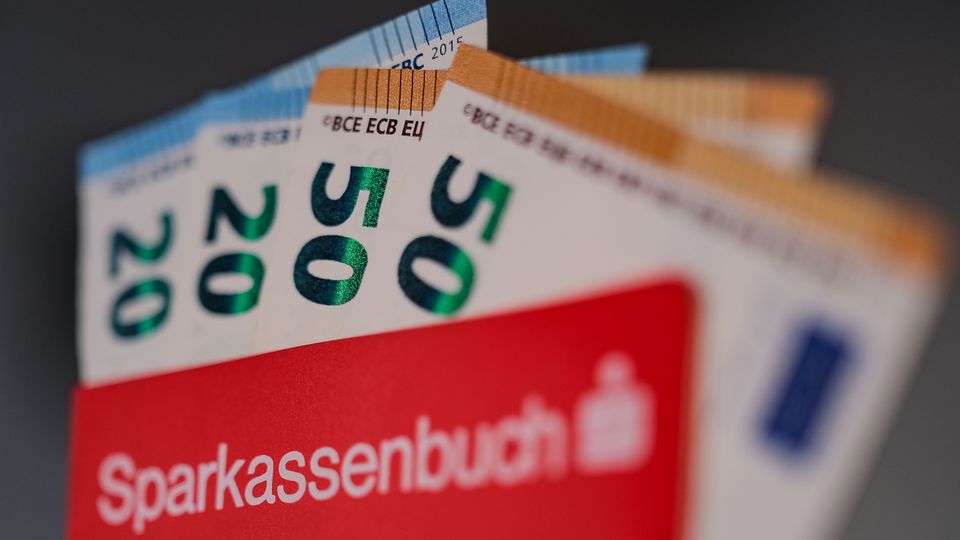

Germans save religiously. The Sparquote (savings rate) hovers around 10-11%, among the highest in the developed world. The average household stashes €270 monthly. Yet this virtue becomes a vice when the money lands in Tagesgeldkonten earning negligible interest.

According to DZ Bank, German households hold €3.4 trillion in cash and deposits, over one-third of total financial assets. Meanwhile, equities represent just €880 billion (9.4%). While inflation runs at 3-4%, these "safe" savings lose purchasing power daily. It’s like filling a bathtub with the drain open, yet calling it "responsible."

The psychological trap is loss aversion: the pain of losing €1,000 outweighs the pleasure of gaining €1,000. When Germans see 7% annual returns, they focus on the potential 20% drop, not the long-term compound growth. As one commenter observed, "People see €1,000 invested and think: ‘I could lose it all!’ Not: ‘I could have €70 more next year, then €150, then €500.’"

Where Financial Education Goes to Die

German schools teach advanced mathematics but not compound interest. They explain the Reformation but not the difference between an ETF and a speculative penny stock. Financial literacy is left to parents, who, as we’ve established, are traumatized, and to bank advisors with quotas to hit.

The result? A nation that confuses Spekulation with Investition. Buying a single stock based on a hot tip is gambling. Buying a diversified global ETF and holding it for 20 years is investing. But without education, both look identical. Young adults open Trade Republic accounts, buy meme stocks at all-time highs, lose 30% in a month, and conclude: "See? Aktien sind Scheiße." They never learned about dollar-cost averaging, asset allocation, or that time in the market beats timing the market.

The Finanzbildung gap costs Germany billions. Studies show poor financial literacy correlates with lower wealth accumulation, higher debt, and greater reliance on state pensions. Meanwhile, the wealthy 10%, who do invest, now hold half the nation’s financial assets, widening inequality.

The Sparkasse Problem: When Your Banker Is Your Enemy

For decades, Germany’s Sparkassen and Volksbanken served as trusted financial advisors. They offered coffee, brochures, and "expert" guidance. But their business model relied on selling high-fee, actively managed funds that underperformed the market.

Many Germans still believe their advisor has their best interests at heart. They don’t realize the "expert" is a 24-year-old with sales targets, not a fiduciary. The shift to digital brokers like Trade Republic and Scalable Capital has democratized access but hasn’t solved the education problem. Now people can lose money faster and cheaper than ever.

As one analyst put it: "A random stock picker (or a chimpanzee throwing darts) often outperforms professional fund managers. Yet Germans still pay 1.5% annual fees for 'active management' that rarely beats the index."

The Inflation Blindness

Germans obsess over Sicherheit (security) while ignoring the silent theft of inflation. A 2024 Kantar survey found only 19% of Germans would take higher investment risk for better returns, down from 33% a year earlier. This risk aversion peaks during uncertainty: economic slowdown, job worries, rising prices.

Yet this is precisely when investing matters most. Inflation at 4% means cash loses half its value in 18 years. A diversified portfolio averaging 7% historically doubles every decade. The math is simple, but the psychology isn’t.

The wealthy understand this. The top 10% invest heavily in stocks and funds, compounding their advantage. The bottom 50% keep cash, falling further behind. This wealth gap isn’t just about income, it’s about asset allocation.

A Glimmer of Hope: The Younger Generation

Here’s the spicy part: change is coming. Since 2022, over 3 million Germans have entered the stock market for the first time. The under-40 cohort added 150,000 investors in 2024 alone, bucking the national decline. They’re bypassing traditional banks, using ETFs, and embracing long-term strategies.

This generation didn’t experience the Telekom crash. They see inflation destroying their savings. They understand that with state pensions under pressure (the Rentensystem faces demographic collapse), they must build wealth themselves.

The rise of ETF-Sparpläne (monthly savings plans) reflects this shift. For as little as €25/month, young investors can own thousands of companies globally. The fees are minimal, the diversification maximal. It’s the antidote to both Opa’s trauma and the banker’s greed.

How to Break the Cycle

Overcoming Germany’s investment aversion requires attacking three fronts:

- 1. Education: Mandate financial literacy in schools. Teach compound interest, inflation, and index investing before calculus. Show students that Zeit im Markt schlägt Timing (time in the market beats timing).

- 2. Regulation: Ban commission-based advice. Require advisors to act as fiduciaries. Force banks to disclose that their "special" funds underperform cheap ETFs.

- 3. Psychology: Reframe risk. The real risk isn’t a 20% market drop, it’s guaranteed 4% annual loss to inflation. Start small: €50/month in a global ETF. Watch it grow. Let experience replace fear.

The data is clear: German households could add billions in wealth annually by shifting just 10% of their cash holdings to diversified equity funds. The barriers aren’t economic, they’re cultural and educational.

The Bottom Line

Germany’s investment skepticism isn’t irrational, it’s learned from real trauma. But it’s also obsolete. The Telekom bubble was 24 years ago. Wirecard was fraud, not market failure. Today’s ETFs are the opposite of 1990s speculation: diversified, low-cost, transparent.

The younger generation gets this. They’re building ETF-Sparpläne while their parents clutch Sparbücher. In 20 years, we’ll see which strategy built wealth, and which built regret.

For now, the challenge is clear: turn €10 trillion in sleeping cash into productive capital. The tools exist. The math works. Only the mindset remains stuck in 2000.

Your move, Deutschland.