Swiss banks have a special talent: they can tell you no without ever explaining why. For years, prospective homebuyers have plugged numbers into standard mortgage calculators, only to discover at the bank counter that their definition of “affordable” has nothing to do with reality. The problem isn’t the math, it’s that Swiss lenders play by a rulebook they never fully show you.

Enter a developer who got tired of the guessing game and built something that actually mirrors how Swiss banks think. The result is a reverse mortgage calculator that doesn’t ask what house you want, it tells you what house you can get.

The Affordability Mirage

Traditional mortgage tools work backwards. You input a property price, and they spit out monthly payments. But in Switzerland, that’s like calculating fuel costs for a car you can’t legally drive. The real gatekeepers are the Swiss Bankers Association affordability guidelines, which mandate that housing costs cannot exceed 33% of gross income. Simple enough, except “housing costs” don’t mean your actual mortgage payment.

Banks use imputed interest rates, typically 5% or higher, to stress-test your finances. They’re not interested in today’s 1.7% rate, they want to know if you can survive when rates hit 5% tomorrow. Add amortization obligations for the second mortgage, Nebenkosten (ancillary costs) of 1% of property value, and maintenance assumptions, and suddenly your “affordable” CHF 800,000 apartment requires an income that would make a pharma executive blush.

This is where most calculators fail. They show you the payment. They don’t show you the bank’s real calculation.

Flipping the Equation

The developer behind mortgagecalculator.ch recognized this gap after conversations with friends about housing costs. The frustration was universal: everyone knew the 33% rule existed, but nobody could reverse-engineer it to find their actual ceiling. So he spent weeks building a tool that does exactly what banks do, calculate maximum borrowing capacity from income and assets, not the other way around.

The calculator’s genius is its fidelity to Swiss banking logic. It doesn’t just slap a 33% multiplier on your salary. It builds the full affordability picture:

- Imputed interest stress test (defaulting to 5%, though customizable)

- Mandatory amortization for the second mortgage (up to 15% of property value, must be paid down within 15 years)

- First mortgage ceiling (65% of lending value, interest-only permitted)

- Down payment composition rules (minimum 20% total, with specific restrictions on Pillar 2/3a usage)

- Cantonal variations (still in development, but acknowledged as critical)

The Pillar Problem Nobody Talks About

Early versions of the calculator contained a critical flaw that revealed just how misunderstood Swiss mortgage rules are, even among financial professionals. The developer initially capped Pillar 2 withdrawals at 10% of the property value, reflecting a common misconception.

The reality is more nuanced. FINMA guidelines require 10% of the lending value to come from non-Pillar 2 sources. Once that threshold is met, you can withdraw additional Pillar 2 funds up to your vested benefits balance. You could theoretically finance a CHF 1 million property with CHF 100,000 in cash and CHF 100,000 from Pillar 2, if your pension fund allows it.

Even more strategically, you can pledge Pillar 2 assets instead of withdrawing them. This keeps your retirement capital invested, avoids immediate tax consequences, and preserves disability and survivor benefits. The trade-off? A larger mortgage and higher interest costs. The calculator now models both options.

Pillar 3a follows similar logic. While early versions treated it like a capped resource, the rules allow full withdrawal for homeownership, again, with tax implications that savvy borrowers factor into their decisions.

When the Community Stress-Tests the Tool

The calculator’s development followed a pattern familiar to Swiss precision engineering: release, critique, refine. Users quickly identified gaps that would have tripped up real-world applicants.

Down payment flexibility was the first fix. The original version forced a 20% cap, but many Swiss buyers want to put down more, sometimes 35% or 50%, to avoid the second mortgage entirely. The updated version includes a slider up to 50%, though the UI initially confused users with contradictory “cap” and “slider” options.

Amortization logic revealed a deeper issue. When a user with CHF 1.2 million in savings and CHF 60,000 income tested the tool, it still generated a second mortgage despite the loan-to-value ratio being under 20%. Swiss rules clearly state: once you hit 35% down payment, amortization requirements disappear. The developer fixed this, but the bug highlighted how counterintuitive Swiss mortgage structuring can be.

Buying costs emerged as another blind spot. A user pointed out that notary fees, property transfer taxes, and registration costs, typically 1.5% to 5% depending on the canton, can kill a deal after you’ve mentally spent your last franc on the down payment. In Zurich, these costs are lower (around 0.5-1%), while Geneva and Vaud can hit 5%. The developer added this to his roadmap, but for now, users must manually factor it in.

The 33% Rule’s Dirty Secret

Here’s what banks won’t say: the 33% rule is negotiable, if you’re wealthy enough. High-net-worth individuals with substantial assets can sometimes push to 35% or even 40%, particularly if they have liquid investments that demonstrate capacity to weather rate shocks. The calculator doesn’t model this because it’s not standard policy, but it’s a reminder that Swiss banking is still relationship-driven.

More importantly, the rule applies to gross income, not net. For a couple earning CHF 150,000 combined, that’s CHF 4,125 per month for housing costs. But after taxes, AHV/AVS, BVG/LPP, and Krankenkasse, their net might be CHF 110,000, making that CHF 4,125 feel much heavier. The calculator shows the gross calculation because that’s what banks use, but savvy users mentally adjust downward.

Cantonal Chaos and the Next Frontier

The developer admits cantonal differences remain unaddressed. This isn’t trivial. A property in Zurich faces different transfer taxes than one in Geneva or Ticino. Notary costs vary. Some cantons require additional guarantees. The calculator’s current “CantonBetaZH, Zürich” label hints at future localization, but for now, it’s a one-size-fits-most solution.

The next iteration might include:

– Cantonal tax calculators for transaction costs

– Pledge vs. withdrawal optimization for Pillar 2

– Sensitivity analysis for rate shocks beyond 5%

– Integration with actual bank affordability models (if banks ever open their APIs)

Why This Matters Now

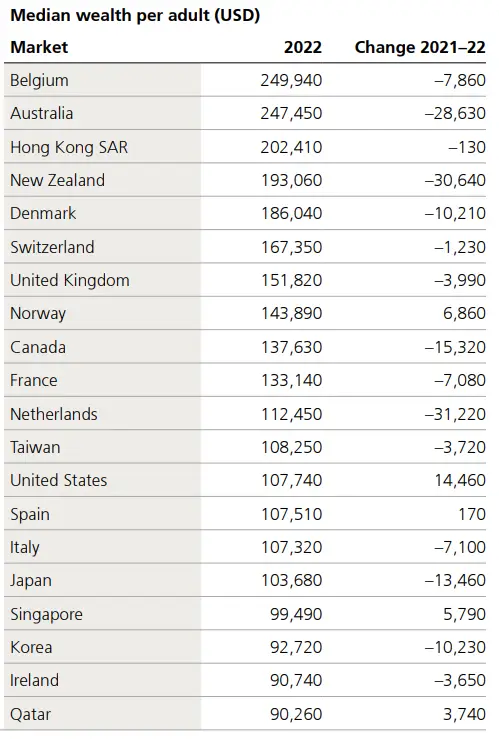

Swiss property prices have outpaced income growth for a decade. The median home in Zurich now costs over CHF 1.5 million, requiring an income of CHF 250,000+ to meet affordability rules. In Geneva and Lausanne, the situation is similarly brutal. The dream of Eigenheim is fading for middle-class families.

Tools like this democratize information. They don’t change the math, but they change who understands it. Instead of walking into a bank blind, you can arrive knowing your exact numbers, questioning their assumptions, and negotiating from knowledge rather than hope.

The calculator also reveals uncomfortable truths. That couple earning CHF 150,000? They can afford roughly CHF 850,000 under standard rules, enough for a 2.5-room flat in Zurich’s outer districts, not the family home they imagined. The tool doesn’t soften this blow, but it delivers it early, privately, and without a banker judging your Excel skills.

The Verdict: Does It Work?

For a free tool built by one developer, mortgagecalculator.ch is remarkably accurate. It mirrors the calculations used by major Swiss lenders and incorporates the nuances that trip up generic calculators. The community-driven improvements have made it more robust, and the transparency about its limitations (cantonal costs, UI quirks) is refreshing.

But it’s a starting point, not a finish line. Real bank approvals involve credit checks, employment history verification, and subjective risk assessment. A calculator can’t capture whether your boss likes you enough to confirm your bonus structure or if your freelance income is “stable enough” for UBS.

Use it to set realistic expectations. Use it to compare scenarios: What if I save another CHF 50,000? What if I pledge instead of withdraw? What if I buy in a cheaper canton? Use it to walk into that bank appointment with confidence, knowing the difference between their jargon and your actual numbers.

The Swiss housing market isn’t getting more affordable. But at least now, you can know exactly how unaffordable it is, before you fall in love with a property you’ll never get.

Bottom line: If you’re serious about buying property in Switzerland, run your numbers here first. Then run them again with a 6% imputed rate. Then speak to a mortgage broker. The tool won’t buy you a house, but it will stop you from wasting years chasing one that’s mathematically out of reach.