German tax law promises to ease the burden of commuting. The reality? For many drivers, the Pendlerpauschale functions more like a symbolic gesture than actual financial relief. While the allowance inches up to 38 cents per kilometer in 2026, the true cost of car ownership has already surged past 87 cents per kilometer. That gap transforms every commute into a slowly deepening financial hole, one that costs typical long-distance workers between €500 and €1,000 every month.

The Math That Hurts: 38 Cents Against 87

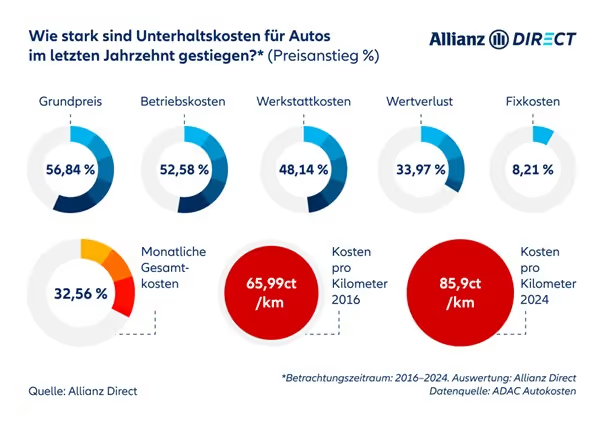

Let’s cut through the political talking points and run the numbers. The ADAC calculates that operating a car in Germany cost an average of 87.56 cents per kilometer in 2024. That figure isn’t plucked from thin air, it aggregates depreciation, insurance, maintenance, taxes, and fuel for a five-year ownership period.

Now compare that to what the tax office actually recognizes. Until 2026, the Pendlerpauschale grants 30 cents per kilometer for the first 20 kilometers, then 38 cents beyond that. From January 1, 2026, it becomes a flat 38 cents from the first kilometer. Sounds generous in a press release. In practice?

A commuter traveling 50 kilometers each way to work, common in regions like Bavaria or Baden-Württemberg where housing costs push workers outward, covers 2,000 kilometers monthly. At 87.56 cents, the real cost hits €1,751.20. The tax deduction? At 38 cents, that’s €760. The raw gap: €991.20 per month. Even after accounting for the tax deduction’s actual value (more on that later), the out-of-pocket loss easily exceeds €500 monthly.

What the Finanzamt Actually Gives You

Here’s where confusion costs taxpayers real money. The Pendlerpauschale doesn’t work like a mileage reimbursement from your employer. It’s a deduction from your taxable income, not a direct refund of expenses.

If you earn €50,000 annually and claim €4,000 in commuter allowances, your taxable income drops to €46,000. At a 35% marginal tax rate, that €4,000 deduction saves you €1,400 in taxes. You still spent €4,000 (or more) on commuting. The state didn’t cover your costs, it simply taxes you slightly less.

This distinction gets lost in political rhetoric. Ministers praise the increased allowance as “relief for commuters”, but the Finanzamt never pretended to subsidize travel fully. The policy aims to acknowledge work-related expenses, not eliminate them. Yet for workers in regions with poor public transport, the practical effect is a mandatory, uncapped financial loss.

Why ADAC’s Numbers Feel Too High (Until You Check Your Bank Account)

Critics often attack the ADAC figures as unrealistic. Their methodology assumes a new car, five-year ownership, and 15,000 kilometers annually. Many commuters drive older vehicles or rack up 30,000+ kilometers yearly.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: even “optimistic” calculations hurt. One analysis from the research data showed a driver with a three-year-old car, kept for five years, calculating costs at 34.25 cents per kilometer, still below the ADAC average but far above the tax allowance. That calculation excluded unexpected repairs, parking fees in city centers (€200-400 monthly in Frankfurt or Munich), and the financial shock of early replacement.

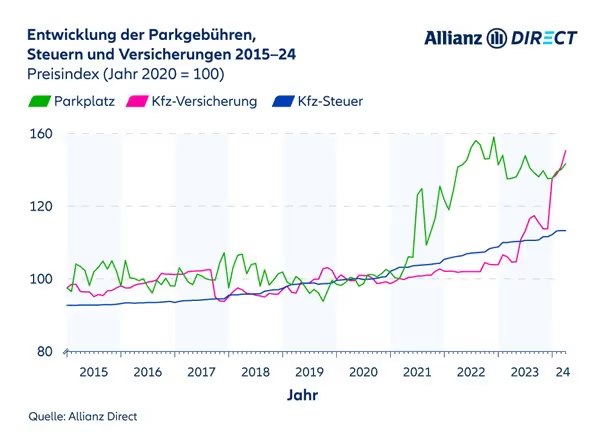

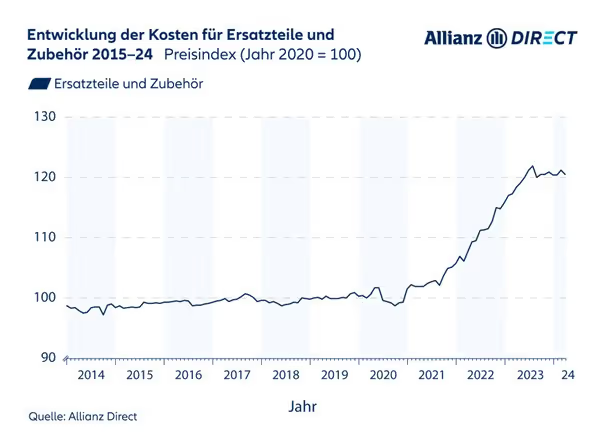

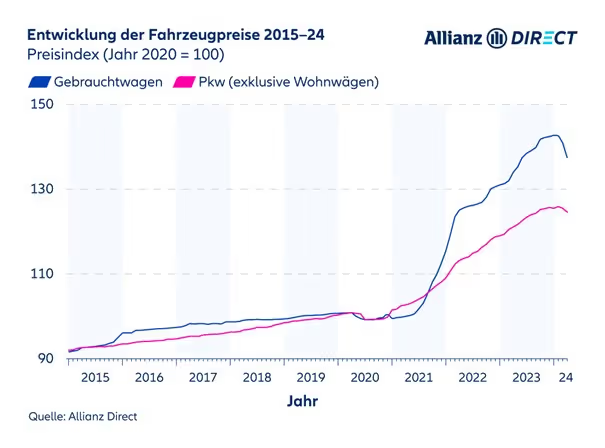

The ADAC numbers sting because they reflect German automotive reality: insurance premiums rose 33.9% in a decade, workshop costs jumped 48%, and vehicle prices surged 56.84% for new cars. Even frugal drivers can’t outrun these trends.

The Policy Gap: Designed for a Different Era

The Pendlerpauschale originated when most workers lived near factories and drove modest distances. Today’s housing market shattered that model. A worker in Berlin’s affordable outskirts might drive 40 kilometers to the city center. A technician in rural Saxony could face 80 kilometers to the nearest industrial park.

The 2026 reform, 38 cents from kilometer one, addresses political pressure but not the structural mismatch. As critics in the Bundesrat debate noted, the allowance remains “neither fair nor climate-friendly.” It subsidizes long commutes without requiring alternatives, locking in car dependency.

Worse, the benefit flows disproportionately to higher earners. A top-bracket taxpayer saves 45 cents per deducted euro, a low-wage worker saves perhaps 14 cents. The policy helps those who need it least, while the working middle class absorbs the real cost.

The Hidden Costs That Break the Budget

The 87.56 cent figure breaks down into painful specifics:

– Depreciation: New cars lose 20% value immediately, then 15% annually. A €35,000 vehicle costs €5,250 yearly in lost value alone.

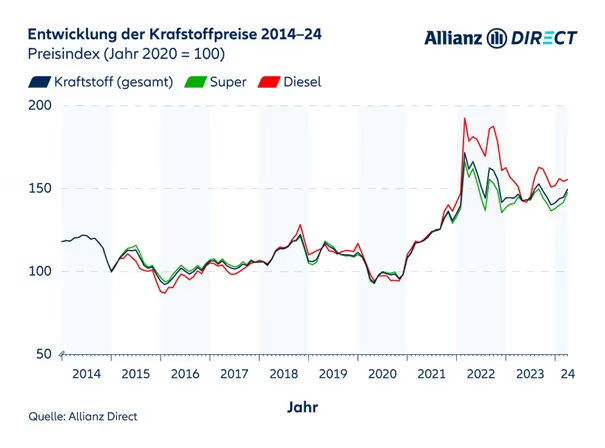

– Fuel: At €1.65/liter and 7L/100km, a 100km daily commute costs €231 monthly. Diesel drivers paid 50.8% more over the last decade.

– Insurance and Tax: Comprehensive coverage for new cars runs €800-1,200 annually. Vehicle tax adds another €200-600 depending on emissions.

– Maintenance: The 48% surge in workshop costs reflects modern cars’ complexity. A single sensor replacement can exceed €500.

– Tires and Extras: Winter and summer sets, storage, and seasonal changes add €400+ every two years.

These numbers exclude parking tickets, car washes, and the occasional fender-bender. They also ignore opportunity cost, money tied up in a depreciating asset instead of earning returns elsewhere.

Who Actually Profits (Spoiler: Not Commuters)

Some argue the Pendlerpauschale was never meant to cover costs fully, that it simply recognizes unavoidable expenses. But this logic collapses when examining regional inequality. Workers in Berlin, Hamburg, or Munich have public transport alternatives. Rural commuters in Brandenburg or Bavaria often don’t.

The policy effectively punishes those forced to drive. It also discourages efficient choices: a hybrid driver gets the same deduction as a gas-guzzling SUV pilot, despite vastly different environmental and financial impacts. The new flat rate from 2026 removes even the modest incentive for shorter commutes that the 21-kilometer threshold once provided.

The Tax Return Reality Check

Claiming the allowance requires meticulous records. The Finanzamt demands the one-way distance, number of workdays, and proof if audited. Many workers underclaim from confusion, others overclaim and face corrections.

The €4,500 annual cap for non-car travel highlights the policy’s car-centric bias. Use public transport exclusively, and your deduction maxes out. Drive a 50km route, and you can deduct €4,750 annually (250 days × 50km × 38 cents). The system nudges workers toward car ownership, even when trains or buses exist.

Practical Strategies to Shrink the Gap

You can’t change tax law overnight, but you can limit the damage:

- 1. Run Your Actual Numbers: Track every auto expense for three months. Use apps like Vimcar or simple spreadsheets. Most drivers underestimate costs by 30-50%.

- 2. Optimize Your Car Choice: The ADAC data shows small cars cost 30-40% less per kilometer. A used Dacia or Skoda Fabia can slash your gap significantly. Electric vehicles benefit from tax exemptions and lower running costs, though higher purchase prices complicate the math.

- 3. Negotiate Remote Work: Even two home office days weekly cuts your commuting costs by 40%. German labor law increasingly supports such requests.

- 4. Relocate Strategically: Moving 10 kilometers closer saves €175 monthly at real cost levels, often outweighing higher rent.

- 5. Maximize Tax Deductions: Claim everything, parking, car washes, even the ADAC membership fee. Use Anlage N correctly and consider professional tax software.

- 6. Challenge the Narrative: Contact your Bundestag representative. The 2026 reform passed with little debate about actual cost coverage. Pressure for a mileage-based, vehicle-type-adjusted allowance could build momentum for real change.

The Bottom Line: A Systemic Problem, Not a Personal Failing

The €500-1,000 monthly loss isn’t about poor financial planning. It’s a policy choice. Germany funds highways while starving rail, offers tax breaks for company cars while underfunding public transit, and pretends a 38-cent deduction offsets 87 cents of real cost.

For commuters, the math is stark: every 100 kilometers driven costs roughly €50 out-of-pocket after tax benefits. Over a year, that’s €12,000 in uncompensated expense, enough for a down payment on a home closer to work, or a year of retirement savings.

Until the Pendlerpauschale reflects actual costs or Germany invests in alternatives, workers face a hidden tax on employment. The allowance increase in 2026 helps, but it’s a Band-Aid on a hemorrhaging wound. The real solution requires either moving closer to work, changing jobs, or demanding policy that acknowledges what driving in Germany truly costs.

Your commute is probably more expensive than you think. And the Finanzamt only cares up to 38 cents on the euro.