The podcast clip hit German social media like a bombshell: a politician claiming that a family earning €3,000 gross might have more money left over than one earning €5,000. The statement sounded absurd, until you dig into the mechanics of Germany’s tax and transfer system. Suddenly, that counterintuitive claim reveals a structural problem that affects thousands of families navigating the treacherous waters between low-income support and middle-class stability.

The Shocking Math Behind the Claim

The controversy started when FDP politician Nicole Büttner-Thiel stated on a podcast that someone earning €3,000 gross could end up with more disposable income than someone earning €5,000. The internet erupted. Commenters called it political spin, others shared personal experiences, and a few demanded to see the actual calculations.

The reality is more nuanced than the headline suggests, but the underlying phenomenon, known as the “transfer withdrawal rate” or Transferentzugsrate, is very real. As your gross income rises from €3,000 to €5,000, you don’t just pay more taxes and social contributions. You also lose access to a patchwork of benefits: Wohngeld (housing benefit), Kinderzuschlag (child supplement), subsidized kindergarten fees, and other social transfers that can total hundreds of euros monthly.

A chart from the Federal Ministry of Finance shows how this works in practice. For a four-person family, the available income barely increases, and can even dip slightly, when gross earnings rise from €3,000 to €4,000. Only after crossing certain thresholds does net income start climbing again.

How Germany’s Benefit System Creates a 100% Marginal Tax Rate

The core issue isn’t the income tax itself, though Germany’s progressive rates certainly play a role. The real culprit is how benefits phase out as income rises. For every additional euro you earn, you might lose one euro in benefits, creating an effective marginal tax rate of 100%.

Let’s break down what happens when a family’s income climbs from €3,000 to €5,000 gross:

- At €3,000 gross:

– Low income tax due to Grundfreibetrag (basic tax-free allowance)

– Full eligibility for Wohngeld, which can cover a significant portion of rent

– Kinderzuschlag of up to €292 per child monthly

– Reduced or free kindergarten fees (Kitabeiträge) depending on the municipality

– Potential eligibility for additional local subsidies - At €5,000 gross:

– Higher income tax bracket kicks in

– Sozialabgaben (social security contributions) increase proportionally

– Wohngeld phases out completely

– Kinderzuschlag disappears

– Kindergarten fees rise to full market rate

– All other means-tested benefits vanish

The result? That extra €2,000 in gross income might translate to just €100-200 in actual disposable income, or in some specific scenarios, nothing at all.

The Munich Family Example That Went Viral

The most cited example involves a family with two children in Munich. With €3,000 gross income, they qualify for maximum Wohngeld (which in Munich’s brutal rental market can exceed €800), full Kinderzuschlag, and subsidized Kita fees. Their net disposable income after housing and childcare might be around €2,200.

Push that gross income to €5,000 and the picture changes dramatically. The Wohngeld disappears entirely. Kinderzuschlag stops. Kindergarten fees jump from €50 to €400 per child. Despite earning €2,000 more gross, their disposable income might be €2,250, just €50 higher for significantly more work and stress.

This isn’t theoretical. Many international residents report similar experiences when negotiating salary increases or considering full-time versus part-time work. The system punishes ambition in this specific income band.

Beyond Income Tax: The Hidden Benefit Cliff

What makes Germany’s system particularly tricky is that these benefit phase-outs happen at different income levels and vary by location. A family in Berlin faces different Wohngeld thresholds than one in Stuttgart. Kindergarten fees in Bavaria follow different rules than in North Rhine-Westphalia.

The KfW Wohneigentum für Familien program illustrates this complexity perfectly. To qualify for subsidized home loans, a family with one child must have a taxable income below €90,000. With two children, the threshold rises to €100,000. Earn one euro more, and you lose access to interest rates that can be four percentage points below market rate, potentially costing thousands annually.

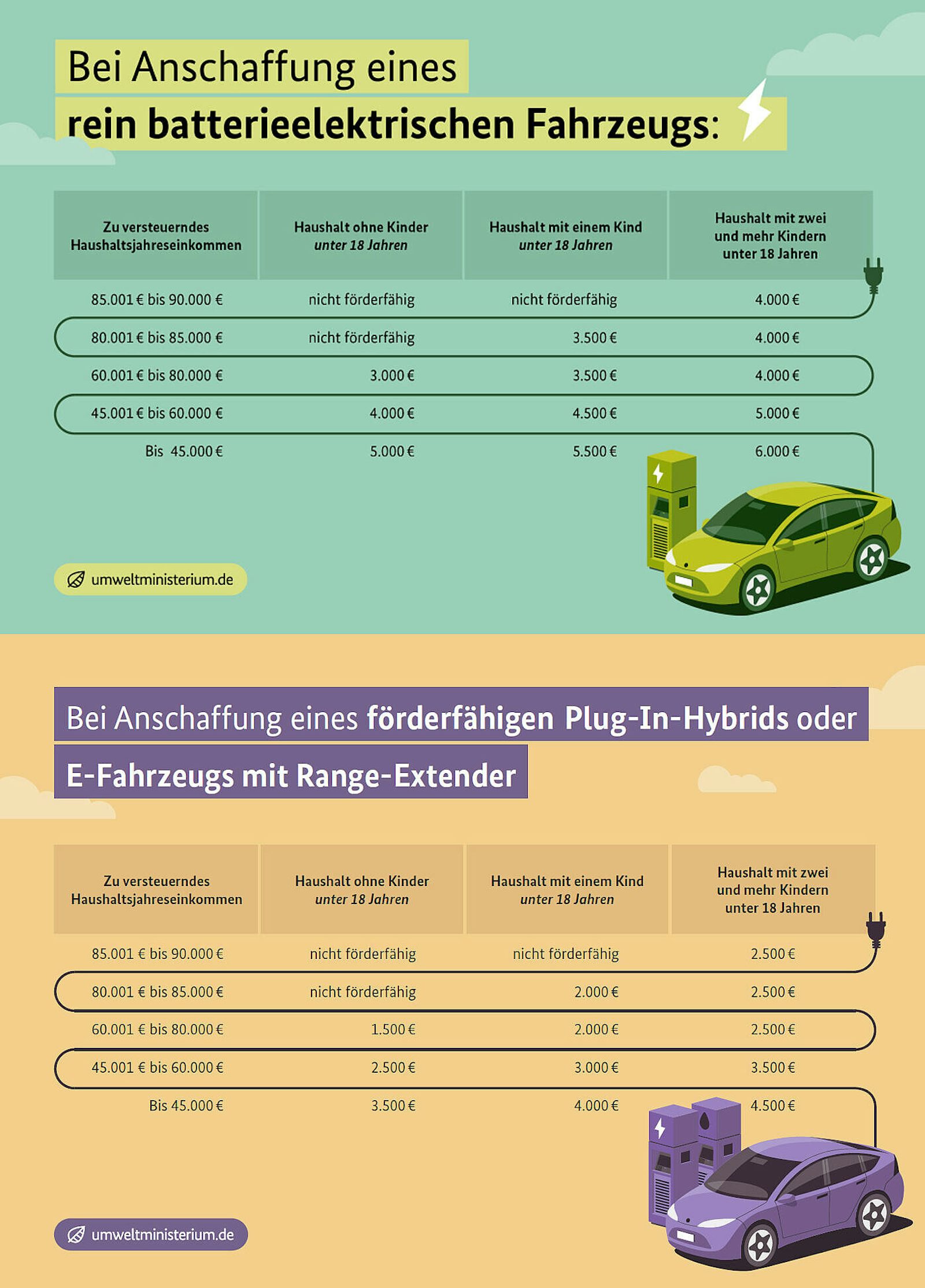

Similarly, the new E-Auto-Förderung (electric car subsidy) demonstrates the same principle. A household earning €45,000 gets €2,000 more in subsidies than one earning €60,000. The incentive structure actively discourages crossing income thresholds.

The Political Debate and Proposed Solutions

CDU General Secretary Carsten Linnemann has called for raising the threshold for the Spitzensteuersatz (top tax rate) from €68,000 to €80,000 gross annually, arguing that middle-income earners face excessive burdens. The SPD, meanwhile, wants to increase the top tax rate itself to 47% and impose social security contributions on capital income.

Both approaches miss the core problem: it’s not just about tax rates, but about the interaction between taxes and benefits. The infamous Mittelstandsbauch, the middle-class tax bump, describes how earners between €30,000 and €60,000 face disproportionately high marginal rates. Combine that with benefit phase-outs, and you get the €3,000 vs €5,000 paradox.

Economists argue the solution isn’t higher taxes or lower benefits, but a more gradual phase-out of transfers. Instead of cutting €800 in Wohngeld at a single threshold, reduce it incrementally so that earning more always leaves you better off.

What This Means for Your Career Decisions

If you’re negotiating a salary increase from €3,500 to €4,500 gross, don’t just look at the gross number. Calculate your actual net gain after:

- Higher Sozialabgaben: Your contributions to pension, unemployment, health, and nursing care insurance

- Increased income tax: Moving into higher brackets

- Lost benefits: Wohngeld, Kinderzuschlag, Kita subsidies

- Reduced eligibility: For future programs like KfW home loans or e-car subsidies

In some cases, accepting a part-time position or staying at 80% employment might actually increase your effective hourly compensation. The math is uncomfortable but undeniable.

Practical Steps to Navigate the System

1. Calculate your true marginal rate: Use online calculators that factor in both taxes and benefit phase-outs. The official German tax calculators often miss the transfer withdrawal effects.

2. Time your income increases: If you’re close to a benefit cliff, consider spreading a raise over multiple years or negotiating non-monetary benefits like additional vacation days.

3. Understand local variations: Research your municipality’s Kita fee structure and Wohngeld thresholds. These can swing your calculation by hundreds of euros.

4. Consider the long game: Some benefits, like KfW home loans, look at your income from two years prior. A temporary income spike might disqualify you from decades of subsidized mortgage rates.

5. Get professional advice: A good Steuerberater (tax advisor) familiar with Sozialleistungen (social benefits) can model different scenarios. The €200 consultation fee could save you thousands.

The Bigger Picture: Why Germany Needs Reform

This isn’t about “lazy workers” or “welfare abuse”, it’s about rational responses to poorly designed incentives. When the system punishes earning more, people optimize accordingly. Germany faces a shortage of skilled workers, yet its own policies discourage full-time employment for parents and middle-income earners.

The debate touches a nerve because it exposes a fundamental tension: Germany wants to be both a high-tax social welfare state and a dynamic economy. The current system achieves neither, trapping families in a bureaucratic maze where the rules change at arbitrary income levels.

Bottom Line: Do Your Homework Before Celebrating That Raise

The €3,000 vs €5,000 claim isn’t universal truth, it’s a warning. For single earners without children, the standard logic holds: more gross income means more net income. But for families with children, especially in high-cost cities, the benefit cliff is real and painful.

Before you accept that promotion or extra work hours, run the numbers. Factor in every benefit you’ll lose and every new expense you’ll incur. Sometimes the smartest financial move is saying no to more gross income, and yes to more time, less stress, and a system that doesn’t penalize ambition.

The German government is slowly waking up to this issue, with proposals to smooth benefit phase-outs and raise tax thresholds. But change takes time. Until then, you’re on your own to navigate a system where earning more can literally cost you money.

Key Takeaways

- Germany’s benefit phase-outs can create effective marginal tax rates exceeding 100%

- Families with children in expensive cities face the steepest cliffs

- Always calculate net gain after lost benefits, not just higher taxes

- Consider timing and alternative compensation when near benefit thresholds

- The system needs reform, but until then, informed decisions are your best defense

For more on how social security contributions affect middle-income earners, see how social security contributions disproportionately affect middle-income earners in Germany. To understand how small tax differences create big net pay gaps, check out how small differences in tax deductions can lead to significant net pay variations.