You’ve finally hit your number. After years of grinding through German bureaucracy, enduring the GEZ letters, and navigating the labyrinth of Krankenversicherung options, your portfolio sits at that magical threshold where work becomes optional. Now comes the question that separates the spreadsheet warriors from the truly financially independent: how do you actually live off this money without triggering a tax avalanche that makes the Solidaritätszuschlag look like pocket change?

The German FIRE community has been debating this with religious fervor, and the consensus is about as stable as Deutsche Bahn’s summer schedule. The core battlefield: ausschüttende ETFs that pay regular dividends versus thesaurierende ETFs where you sell shares periodically. Both camps have their priests, their scripture, and their horror stories. But here’s what the tax law actually says, and it’s not what your favorite Finanzfluss calculator told you.

The Illusion of the “Tax-Efficient” Accumulating ETF

For years, the conventional wisdom went like this: buy accumulating ETFs, let compound interest work its magic, and sell shares as needed. No dividends to tax, no hassle. This strategy looks brilliant on paper, especially when you factor in Germany’s Abgeltungssteuer of 25% plus Solidaritätszuschlag (effectively 26.375%). The logic seems airtight, defer taxes, maximize compounding, live off capital gains later.

Then came the Investmentsteuerreform 2018 and its nasty little surprise: the Vorabpauschale.

This isn’t some bureaucratic footnote. It’s a pre-emptive tax strike on your accumulating ETFs that fundamentally alters the math. Every January, your broker calculates a fictional gain on your thesaurierende ETFs and taxes you on it, even if you haven’t sold a single share. The calculation is brutal: take 70% of the base interest rate (2.53% in 2025) multiplied by your fund’s value at the start of the year. If your actual gains are lower than this fictional number, you’re taxed on the lower amount. If they’re higher, you’re taxed on the fictional number anyway.

The result? You’re paying taxes on money you never received, on gains you haven’t realized, and you’re doing it every single year. That “tax deferral” advantage? It’s more like tax acceleration with extra steps.

The Distributing ETF Advantage Nobody Talks About

Here’s where it gets spicy. Distributing ETFs pay out dividends quarterly or annually. These dividends are taxed at the same 26.375% rate, but they also qualify for the Teilfreistellung, a 30% exemption for equity ETFs. This drops your effective tax rate to roughly 18.44%. More importantly, these distributions count toward your Sparerpauschbetrag of €1,000 per year (€2,000 for married couples).

If your dividends stay under this threshold, you pay zero taxes. Zilch. Nada.

Meanwhile, your accumulating ETF brother is shelling out Vorabpauschale taxes every January, regardless of whether he needs the money. He’s also burning through his Sparerpauschbetrag with fictional gains, leaving less room for other capital gains when he actually sells shares in retirement.

The counterargument, “but I can just sell shares strategically”, ignores the psychological reality. In a market downturn, selling shares means locking in losses. Distributing ETFs pay dividends based on company profits, not market sentiment. During the COVID crash, dividend cuts were painful but temporary. Forced share sales were permanent.

The Dividend Stock Purists Are Also Wrong

Some German investors abandon ETFs entirely, building portfolios of individual dividend aristocrats. The logic: higher yields, more control, no TER fees. The reality: you’re trading diversification for concentration risk, and the tax treatment is identical to distributing ETFs. Worse, you’re now responsible for tracking 30-40 individual companies, dealing with corporate actions, and manually reinvesting when you don’t need the cash.

One commenter in the German finance community reported living off his portfolio since his mid-30s, claiming 17% annual returns with individual stocks. He also admitted to investing 15 hours weekly in research, hardly the passive income dream retirement promises. For most, this is a job, not a retirement.

The “Günstigerprüfung” Goldmine

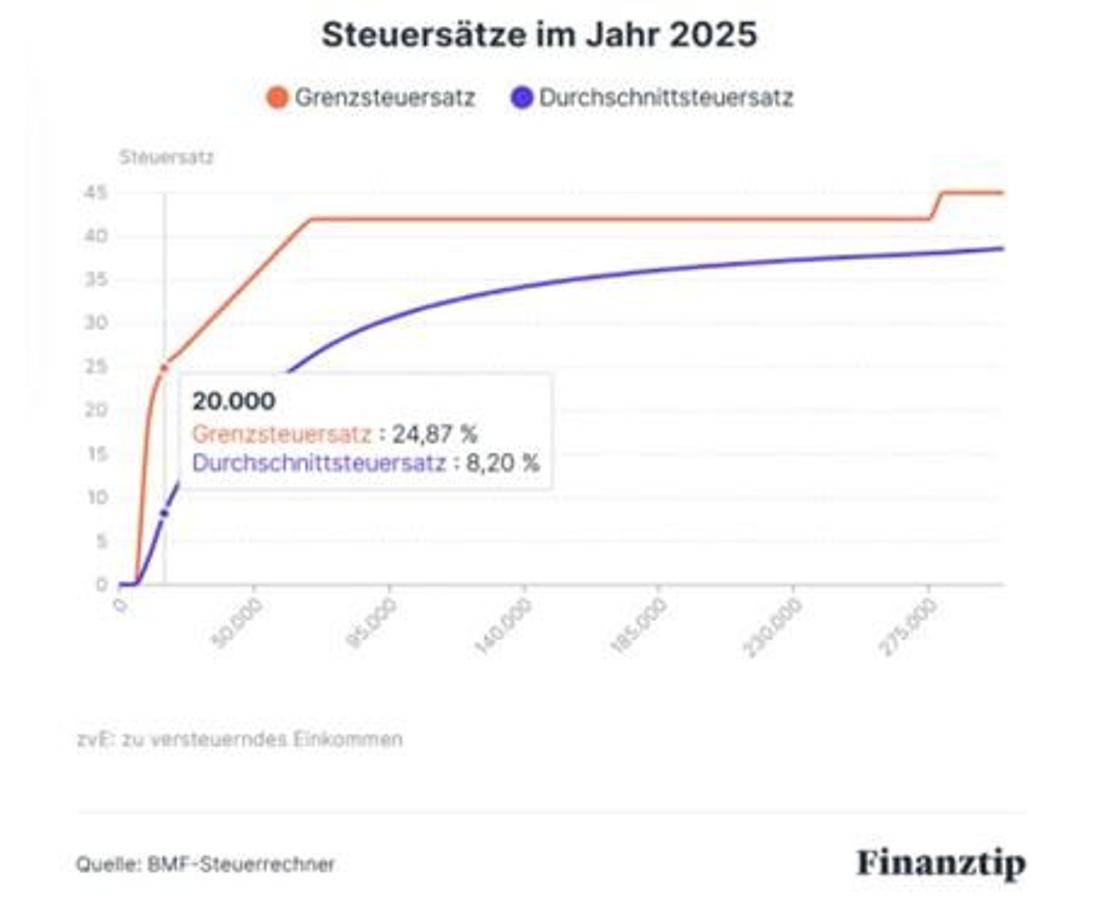

Here’s where the German tax code accidentally helps retirees. The Günstigerprüfung is a tax assessment that compares your marginal income tax rate to the flat 26.375% capital gains rate. If your marginal rate is lower, common for retirees living modestly, you can reclaim the difference.

The magic number? Keep your taxable income under €20,000, and this almost always works in your favor. A retiree with €10,000 in capital gains could reclaim around €500 annually just by filing a proper tax return. Many international residents miss this entirely, assuming the flat tax is final.

This is where accumulating ETFs create another headache. The Vorabpauschale taxes are withheld automatically, forcing you to file for refunds. Distributing ETFs with dividends under your Sparerpauschbetrag? No withholding, no paperwork, no waiting for refunds.

The Health Insurance Handcuffs

Here’s the grenade nobody mentions: Krankenversicherung. If you’re retired before the statutory pension age, you’re likely in private health insurance. Your premiums depend on your income. Capital gains count as income. Dividends count as income. The Vorabpauschale? Also income, even though it’s fictional.

One early retiree in the forums noted he keeps his accounts under €5,000, selling shares only for major purchases like cars or property. This isn’t just tax planning, it’s health insurance survival. Each euro of declared income potentially increases his premiums by 14-15%.

The accumulating ETF strategy forces you to declare income you never spent. Distributing ETFs let you stay under the radar, especially if you keep distributions modest.

The “Dreitöpfemodell” Debate

German financial advisor Andreas Beck popularized the three-pot strategy: cash reserves, bonds, and equities. The idea is to avoid selling equities during downturns. Critics argue it’s overly complex and costs returns. Supporters claim it prevents panic selling.

The reality? It’s psychological scaffolding. If you can stomach selling shares when markets are down, you don’t need three pots. If you can’t, no spreadsheet will save you. The tax difference between strategies is marginal compared to the behavioral risk of forced selling in a crisis.

The Verdict: Hybrid Is King

Pure strategies are for purists. The optimal German retirement portfolio looks like this:

-

Base layer: Distributing ETFs covering your essential expenses, kept under the Sparerpauschbetrag where possible. This gives you tax-free income that doesn’t require share sales.

-

Growth layer: Accumulating ETFs for long-term compounding, but only in years where you have no other capital gains to report. This minimizes Vorabpauschale impact.

-

Opportunistic layer: Individual stocks only if you genuinely enjoy the research and can beat the market after taxes. For 95% of people, this is a hobby, not a strategy.

-

Tax optimization: File that Steuererklärung. Use the Günstigerprüfung. Track your Vorabpauschale and ensure it’s applied to future sales. This alone can save thousands annually.

The math is clear: in Germany’s tax system, the illusion of tax deferral often costs more than transparent, immediate taxation. Accumulating ETFs work brilliantly during accumulation. In retirement, they become a tax compliance nightmare that solves a problem you no longer have.

The real question isn’t “which ETF?” but “how do I minimize declared income while maximizing actual cash flow?” That’s a German tax riddle worth solving.

Actionable Takeaways

Before you quit your job, run these numbers:

- Calculate your essential expenses. Can they be covered by €1,000-2,000 in annual dividends? If yes, prioritize distributing ETFs.

- Model your Vorabpauschale for accumulating ETFs. Will it exceed your Sparerpauschbetrag? If yes, reconsider.

- Check your Krankenversicherung thresholds. What’s the marginal cost of each additional euro of income?

- File a test Steuererklärung. See if the Günstigerprüfung works in your favor. Most software calculates this automatically.

- Keep 12-18 months of expenses in cash. Not for returns, but to avoid forced share sales in downturns.

The German retirement tax code wasn’t built for FIRE enthusiasts. It assumes you’ll work until 67, collect a pension, and die shortly after. Gaming it requires understanding its assumptions, and then politely ignoring them.

Your accumulating ETF portfolio might have gotten you to retirement. But living off it requires a different playbook. Don’t let the tax tail wag the lifestyle dog, but don’t ignore the tail either. In Germany, it’s a very large, very bureaucratic tail that bites every January.