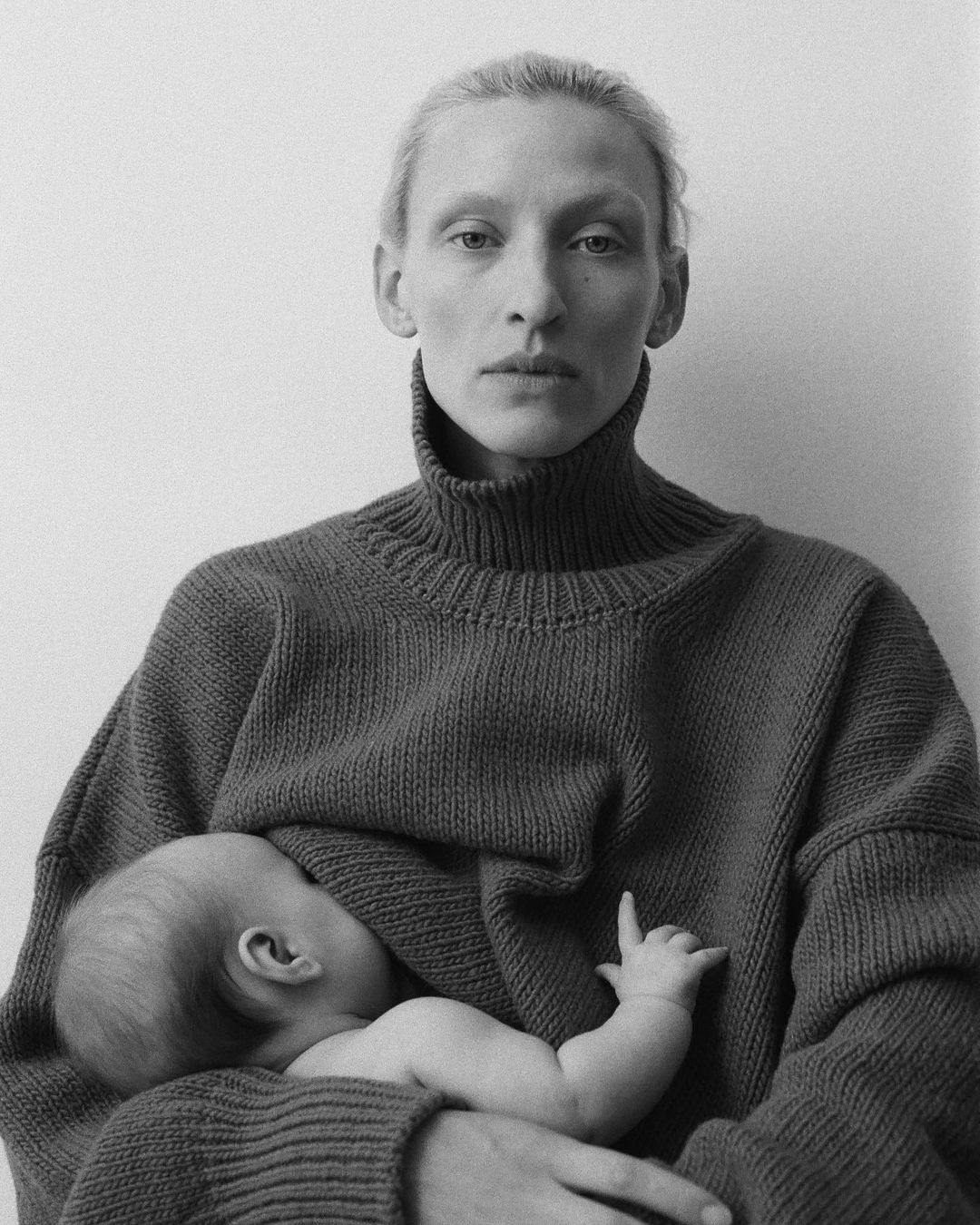

Most Swiss families treat their finances like a Swiss bank vault, impenetrable, private, and definitely not for public consumption. But one couple in Zurich and Thurgau ripped open the curtains on their 2025 financial year, and the view is both inspiring and sobering. This isn’t another generic budgeting guide. This is what actually happens when marriage, a baby, dual careers, and Swiss bureaucracy collide with cold, hard numbers.

The Setup: Two Salaries, One Baby, and a Spreadsheet

He works 80% in finance (the industry, not just the family budget), she’s in office admin at 100%, and they both commute to Zürich from the cantonal borderlands of ZH/TG. In their early 30s, they’ve just navigated the triple-whammy milestone year: marriage, first child, and merging finances completely. Their approach? Full transparency, down to the last Rappen.

The kicker: they’ve been sharing these annual recaps publicly, which makes them either heroes or lunatics in a country where discussing salary is roughly as taboo as putting ketchup on a Rösti.

The Wins: What Went Right in 2025

The Double 3a Coup

Let’s start with the good news, because in Switzerland, maxing out your Säule 3a feels better than finding an empty SBB carriage on a Monday morning. For the first time ever, this couple maxed out both partners’ third pillars. That’s CHF 7,056 per person in 2025, or CHF 14,112 total shielded from taxes and working for their future.

This isn’t just a box-ticking exercise. In the Swiss system, where pension gaps yawn wider than the Gotthard Tunnel, consistently filling your 3a is the difference between a comfortable retirement and surviving on AHV/AVS alone. The fact they pulled this off during a year with a wedding and a newborn is genuinely impressive.

Financial Integration Without Casualties

Last year, they “decided to review” how they handle money, a Swiss euphemism for “we realized our system was a mess.” Post-marriage and mid-pregnancy, they went all-in: both salaries now flow into a joint account, with each partner getting CHF 450 monthly for guilt-free spending. No separate accounts, no score-keeping, no “you paid for the Coop run, I paid for the health insurance” spreadsheet acrobatics.

This is rarer than you’d think. Many Swiss couples keep finances separate indefinitely, citing Eigenverantwortung or just avoiding awkward conversations. Combining finances forces you to agree on priorities, confront spending habits, and, most importantly, unify your approach to Swiss-style compulsory expenses.

The Wedding: Strategic Minimalism

They married in her parents’ garden, booking the entire affair under “travel & activities” in their budget. This wasn’t just frugality, it was a calculated decision knowing what was coming: baby expenses that would make their usual Migros bills look like pocket change.

The Reality Check: Where the Numbers Hurt

The Baby Tax: CHF 1,600 Monthly Impact

Here’s where it gets spicy. The couple estimates that in 2026, they’ll have CHF 1,600 less per month available. Why? Two converging forces: the wife drops to 60% workload, and they start paying for KiTa (Kindertagesstätte).

In Zurich, KiTa costs can run CHF 120-150 per day for infants, even with Gemeinschaft contributions. While subsidies exist in Thurgau, the net out-of-pocket hit for a dual-income couple is substantial. Combine that with losing 40% of one salary, and you’ve got a financial double-punch that no amount of meal prepping can offset.

The Second-Order Baby Expenses

They expected costs, but not the “second-order impacts.” This is where their transparency becomes valuable for anyone planning a family in Switzerland:

- Home appliances: Not just the pram and baby seat, but “going overboard” setting up a dedicated baby room, complete with furniture, monitors, and gear. The punchline? “The baby now prefers to sleep in our bed.”

- Eating out: “We spent a lot on eating out in the months following the birth, justifying it by saying we were too drained to cook.” This is the invisible cost of sleep deprivation. Even in Switzerland, where a kebab costs CHF 12 and a pizza starts at CHF 20, this adds up fast.

- Toiletries & stuff: Pampers burn through budgets faster than a Swisscom roaming charge. Clothes, toys, and miscellaneous baby gear inflated these categories beyond projections.

- Medical expenses: The wife had post-birth complications. With a high-deductible health insurance plan (standard for healthy young adults pre-baby), they covered many costs themselves. In Switzerland, a CHF 2,500 deductible makes sense until it doesn’t.

The Missed Goals: Only Human

They aimed to optimize three recurring expenses but only managed two: swapping a subscription for open-source and changing health insurance. Their main target, switching from UBS to ZKB to save on banking costs, failed because they opened accounts too late. In Switzerland, where bank transfers require more paperwork than a naturalization application, timing matters.

They also fell short on their emergency fund goal, saving CHF 8,500 against a target of CHF 10,000. In a year with a wedding and medical complications, this is hardly failure.

The 2026 Forecast: Tightening the Belt

Looking ahead, their goals are realistic and Swiss-pragmatic:

- Cut eating-out costs by 50%, back to pre-baby levels

- Cap home/furnishing costs at CHF 2,500, no more nesting impulse buys

- Max both 3a pillars again, this will be “tough” with less income

- Optimize three recurring expenses, the ZKB switch is presumably back on

The CHF 1,600 monthly reduction looms large. For context, that’s CHF 19,200 annually, more than many Swiss families save in a good year. Their plan? Presumably, absorb it through reduced discretionary spending and the CHF 900/month they already allocate to guilt-free personal spending.

What This Means for Swiss Families: The Unspoken Math

The 80%/100% to 80%/60% Cliff

This couple’s situation reveals a structural issue in Swiss family planning. The transition from two incomes (even at 80%/100%) to 80%/60% plus KiTa costs creates a negative income shock that hits precisely when expenses peak. Many families discover this too late, after committing to a lease or mortgage based on dual full-time incomes.

The Swiss system assumes family support networks (Grosseltern) or one parent staying home. For dual-career couples without local family, KiTa is the only option, and it’s priced accordingly.

The Health Insurance Trap

Young, healthy couples often choose high deductibles (CHF 2,500) to save on premiums. Pre-baby, this is rational. Post-baby, you face two issues: pediatric care for the child (covered, but with complexities) and unexpected maternal health issues. The comment about post-birth complications highlights a gap in planning, pregnancy is covered, but what comes after might not be fully.

The 3a Priority

Despite everything, they prioritized maxing both 3a accounts. This is the Swiss financial equivalent of “pay yourself first.” Even when cash flow tightens, the tax advantage and long-term compounding make this non-negotiable for anyone serious about retirement. The challenge in 2026 will be whether they can maintain this with CHF 1,600 less monthly.

Actionable Takeaways: What You Can Actually Do

- Model the baby cliff before conception: Calculate your post-baby income (including reduced work percentages) and KiTa costs. If you can’t absorb a CHF 1,500-2,000 monthly hit, adjust your housing or savings expectations now.

- Lock in KiTa spots early: This couple was “lucky to secure a KiTa place from next year.” In Zurich and Thurgau, waiting lists stretch for years. Register during pregnancy, ideally, during the first trimester.

- Review health insurance before trying: Consider lowering deductibles if planning a baby. The premium increase is often less than the out-of-pocket risk for maternal complications.

- Combine finances before major life changes: If you’re planning marriage or a baby, merge accounts at least six months prior. This surfaces spending conflicts and creates a unified budget baseline.

- Automate 3a contributions: Set up monthly standing orders to your 3a providers. If you wait until year-end, life will intervene. Treat it like AHV/AVS, non-negotiable and automatic.

- Budget for “drain” spending: Whether it’s takeout, cleaning services, or convenience groceries, recognize that major life changes increase discretionary spending temporarily. Plan a 20% buffer for the first six months post-baby.

The Bottom Line: Swiss Family Finance Is a Contact Sport

This couple’s transparency reveals what Swiss financial institutions and glossy magazines won’t: family planning in Switzerland is brutally expensive, bureaucratically complex, and financially unforgiving. The CHF 1,600 monthly shock they face in 2026 is the reality for thousands of families who discover too late that the Swiss social safety net assumes traditional family structures that many modern couples don’t have.

Their double 3a victory is admirable, but it’s also a warning. If a finance-savvy couple with two professional incomes struggles to maintain savings momentum, what does that mean for everyone else? The answer isn’t to skip the baby, it’s to budget for the real costs, not the Instagram version.

As they head into 2026 with tighter belts and clearer priorities, their story is a gift to anyone planning a family in Switzerland: plan for the CHF 1,600 shock, or it will plan for you.