For decades, the Swiss dream was “Schaffe, schaffe, Häusle baue” (work, work, build a little house). Now, the unspoken second half of that phrase is “…and pray the bank doesn’t take it when you retire.”

Imagine this scenario: Your parents’ single-family home is worth 1.2 million CHF. There’s a comfortable 400,000 CHF mortgage left on it. Your father, four years from retirement, gets approval to increase the mortgage by 130,000 CHF to buy a rental apartment. You are planning a 130,000 CHF Erbvorbezug (advance inheritance) for your own property purchase. The bank says yes. But then, the hard truth arrives: “Upon retirement, the affordability is not given anymore.” The same institution that approved the leverage now threatens the foundation of the family’s wealth.

This isn’t a hypothetical exercise, it’s a direct summary of a real family’s financial dilemma playing out right now. It cuts to the heart of Swiss financial planning: the collision of intergenerational wealth transfer with stringent banking regulations designed for one life stage, not three.

The Core Conflict: Lifetime Debt vs. Swiss Banking Rules

Swiss banks are not heartless, they are bound by the Tragbarkeitsregel (affordability rule). This regulation states that the total cost of homeownership, interest, amortization, and maintenance, must not exceed one-third of gross income. Banks must apply a “stress test” using a hypothetical interest rate, often around 5%, regardless of your actual fixed-rate deal.

Upon retirement, gross income can drop by 30-50%, transforming a once-comfortable mortgage into a regulatory impossibility overnight. The family in our case study faces a perfect storm: a father wanting to increase leverage at 60, an intergenerational Erbvorbezug, and a looming income cliff at 65.

The bank’s initial “yes” was based on his current salary. Their future “no” is based on his expected AHV (state pension) and Pensionskasse (occupational pension) payouts. The NZZ notes that for a 1M CHF property today, a household needs a gross income of roughly 175,000 CHF to pass this test, a figure far beyond most post-retirement budgets.

The “Erbvorbezug” Gamble: Leveraging One Gift to Finance Another

An Erbvorbezug is a powerful Swiss financial tool allowing parents to gift part of their future inheritance to their children early, often tax-advantaged. It’s frequently used for property down payments, addressing a harsh reality: “Sparen reicht nie, heute muss man erben” (Saving is never enough, today you must inherit), as Donato Scognamiglio of IAZI bluntly told Beobachter. He points out that the price of a typical house in Uster has jumped from 1.2M to 2M CHF in a decade, a gap impossible to bridge by salary alone.

But in this case, the Erbvorbezug creates a double-bind. The father is not only gifting away 130,000 CHF of his liquid capital, but he’s also taking on another 130,000 CHF in debt to invest in a rental property, aiming to generate “passive income.”

Crunching the Numbers: Is the Investment Property a Savior or a Trap?

Let’s break down the math. The father’s current plan involves channeling capital and debt into a new, 530,000 CHF apartment. Expecting a rent of 1,700 CHF inkl. Nebenkosten, the gross rental income might be around 1,500 CHF net. On a 400,000 CHF mortgage at a 1.5% interest rate, the annual cost is 6,000 CHF. Even optimistic calculations show a thin margin. As one financial observer noted, a single major repair, a burst pipe or a 50,000 CHF roof renovation mandated by the Erneuerungsfond, could wipe out years of profit and push cash flow into the red.

This illustrates a critical point often overlooked by new landlords: Swiss rental property is rarely a true “passive income” stream. It’s an active investment with management duties, costs, and risks. The idea that this rental income will seamlessly replace a high salary to satisfy the bank in five years is, at best, a high-stakes gamble.

The Bank’s Dilemma and the Family’s Question

The family’s question is poignant: “Can we provide a guarantee from me and my siblings that we would step in if there were a payment issue?”

The cold, hard answer from banking veterans is: rarely. Banks like UBS and ZKB operate on standardized risk models focused on the primary borrower’s current cash flow. A promise from adult children, while reassuring, is legally complex and often lacks the formal, enforceable collateral a bank requires. It introduces variables, future marriages, debts, job losses, that a bank cannot underwrite. Evidence from forums suggests that while some smaller, cantonal banks (Kantonalbanken) or Raiffeisen might consider family guarantees on a case-by-case basis, the major players typically refuse.

This sentiment is echoed by Florian Schubiger of Hypotheke.ch, who observed in Beobachter a brutal catch-22: “Wer aufstocken will, weil er Geld benötigt, wird den Kredit von der Bank nicht bekommen… Leute, denen die Bank auch im Rentenalter noch eine höhere Hypothek gäbe, hätten schon ausreichend Geld, sodass sie den Kredit zur Mittelbeschaffung eigentlich gar nicht bräuchten.”

In short: if you need the money in retirement, you won’t get the mortgage. If you get the mortgage, you probably didn’t need it.

Pathways Through the Dilemma: What Options Exist?

- Refinance Strategically Before Retirement: Lock in a long-term fixed mortgage now, while income is high. The goal is to secure rates for 10-15 years, pushing the renewal date deep into retirement when the bank might be more flexible if amortization targets are met. As highlighted in another NZZ article, models like Swiss Life’s “Option Flex” are emerging, offering more flexibility for older homeowners who may need to sell unexpectedly.

- Reconsider the Investment Property Plan: This is the most direct lever. Forgoing the 130,000 CHF second mortgage reduces the father’s total debt and improves his debt-to-income ratio post-retirement. The planned Erbvorbezug could still proceed using existing savings, preserving the family home’s financial stability.

- Accelerate Amortization: Use the years before retirement to aggressively pay down the 400,000 CHF mortgage on the primary residence. Every franc paid off before retirement reduces the future income needed to satisfy the bank’s Tragbarkeitsrechnung.

- Explore Pension Lump Sums (Kapitalauszahlung): Part of the Pensionskasse capital can often be taken as a lump sum. Using a portion to pay down the mortgage principal at retirement can dramatically improve the loan-to-value ratio and potentially satisfy the bank, even with lower income.

- Downsize or Rent Part of the Home: While emotionally difficult, converting a part of the large family home into a rental unit (Wohnteil vermieten) can create the verifiable, bank-acceptable income needed to pass affordability checks. It turns an asset into an income stream.

Conclusion: Planning for Three Generations, Not One

The ultimate lesson from this case study is that Swiss property ownership can no longer be planned in isolation. A mortgage taken at 35 must be stress-tested for age 65. An Erbvorbezug must be modeled not just for its tax benefits, but for its impact on the donor’s retirement liquidity. The family home is not just a roof, it’s the central node in a web of intergenerational financial commitments.

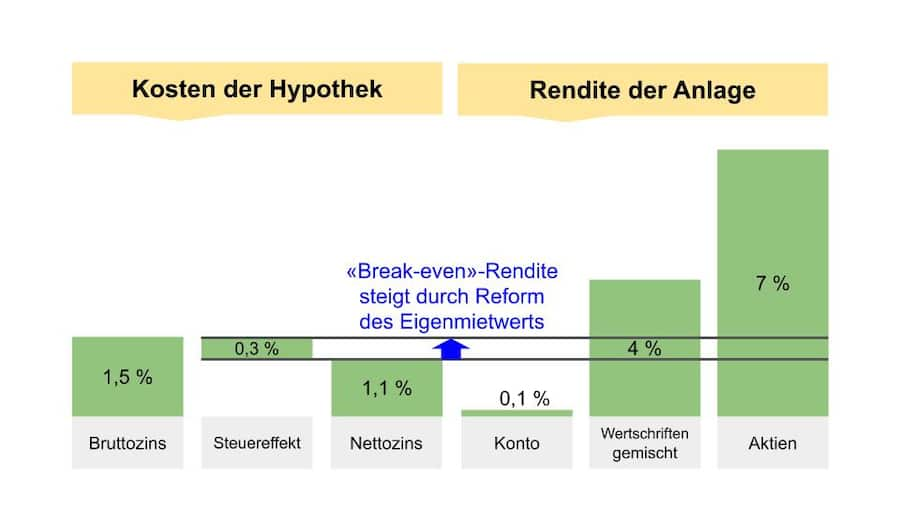

The reform of the Eigenmietwert (imputed rental value) system, phasing out the deduction of mortgage interest (Schuldzinsabzug), makes this calculus even more urgent for retirees. As shown in Beobachter, the net cost of holding a mortgage in retirement is about to rise, squeezing those on fixed incomes further.

The answer to the family’s question is not a simple “yes” or “no.” It’s a conditional “maybe, but only if you radically restructure your plan.” It requires shifting from a strategy of acquiring more to one of securing what you have. The goal must be to arrive at age 65 with a debt profile so conservative that a Swiss bank, with all its regulatory rigidity, cannot argue with the math. Sometimes, the best way to keep everything is to want a little less.