One investor took a year off work, parked their pension in a 75% equity strategy through Frankly, and watched it grow 18% in a year. The kicker? Those gains exceeded what they would have earned by contributing while working. With three decades until retirement, they asked a simple question: why should their money sit in a Pensionskasse earning 1% when markets offer so much more?

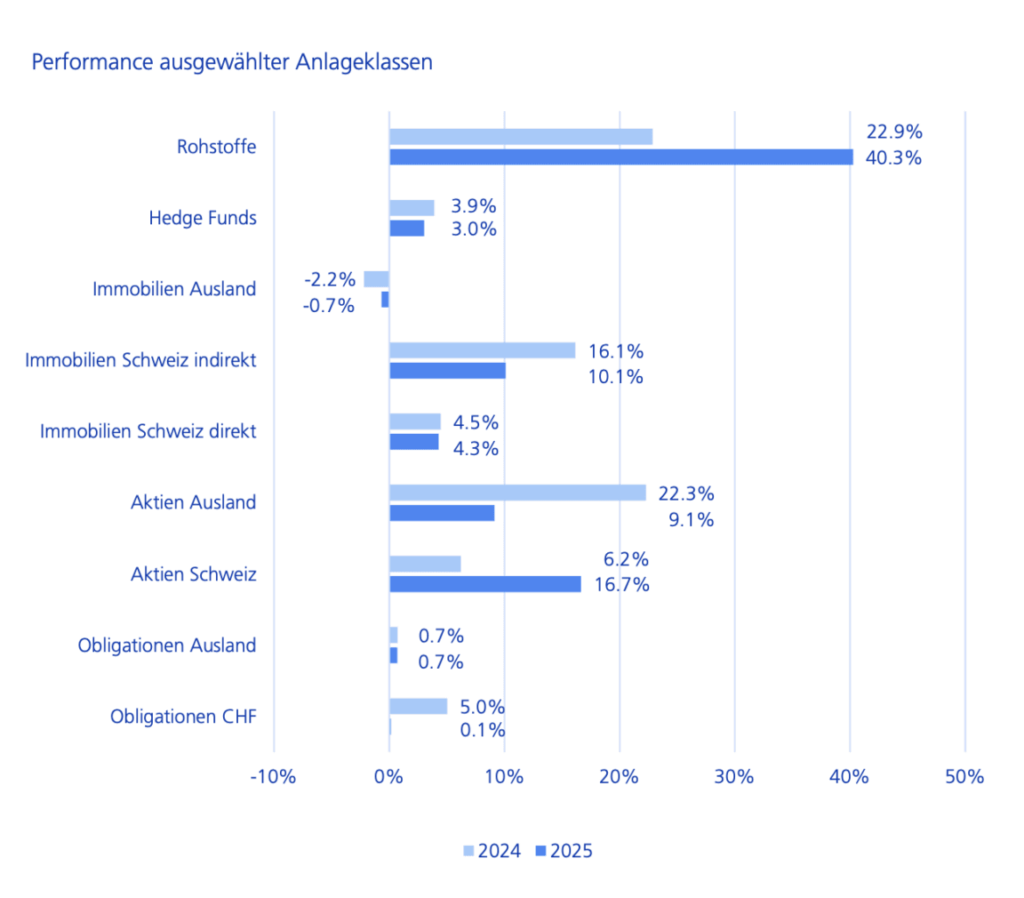

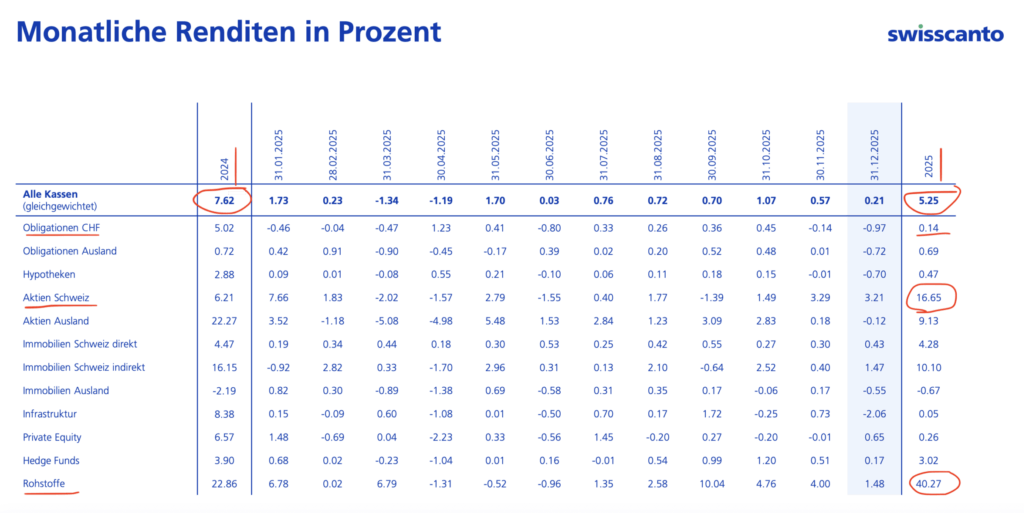

That question cuts to the heart of Switzerland’s pension dilemma. The gap between what individual investors can achieve and what mandatory pension funds deliver has become impossible to ignore. In 2025, Swiss pension funds managed roughly CHF 1 trillion in assets. They generated a solid 5.3% net return, well above the 1.25% minimum required by law, but barely half of what a simple equity index delivered. The difference represents billions in foregone wealth for future retirees.

The Safety-First Trap

Swiss pension funds operate under a unique pressure cooker. Trustees face personal liability for investment losses. Regulators enforce strict coverage ratios. The media screams about any shortfall while ignoring missed opportunities. This creates what industry insiders call a Vollkasko-Mentalität, a comprehensive insurance mindset where avoiding losses matters more than generating gains.

The numbers tell a stark story. According to the latest Swisscanto Pensionskassen-Monitor, funds with higher retiree ratios, those paying out more pensions, delivered just 3.9% returns in 2025. Younger funds with lower payout pressure achieved 5.3%. The spread widens further when you look at the top 10% of performers versus the bottom 10%. The best funds more than doubled the returns of the worst.

Home Bias and the Swiss Stock Heavyweight Problem

Look under the hood and you’ll find another structural issue: home bias. Swiss pension funds keep disproportionate allocations in domestic equities. The five SMI heavyweights, Roche, Novartis, Nestlé, UBS, and Zurich Insurance, accounted for nearly 5% of total pension assets in 2025. When these stocks surged, with Roche up 28% and UBS up 33%, they dragged overall performance upward.

This concentration creates a false sense of security. Yes, Swiss large-caps are stable. But they’re also expensive and represent a tiny fraction of global opportunities. The same funds that benefited from home bias in 2025 missed out on Nvidia’s 38% gain because they held only token positions in global tech. The result? A comfortable but suboptimal portfolio that feels safe while leaving massive returns on the table.

The Generational Time Bomb

Here’s where it gets politically explosive. A 25-year-old software engineer in Zurich faces 40 years of contributions ahead. They can weather multiple market cycles. Their risk capacity is enormous. Yet they’re forced into the same conservative allocation as a 63-year-old nearing retirement.

The math is brutal. Over four decades, the difference between a 5% and an 8% annual return turns a CHF 200,000 contribution into either CHF 1.2 million or CHF 2.2 million. That CHF 1 million gap isn’t theoretical, it’s the difference between a comfortable retirement and genuine financial freedom.

Some pension funds offer 1e plans that allow employees to choose their strategy above a certain salary threshold. But these remain rare and complex. Most workers get a one-size-fits-all solution that fits nobody perfectly.

The Total Portfolio Approach: A Way Forward

Alexandra Tischendorf, Senior Advisor at WTW, argues the solution lies in abandoning rigid strategic asset allocation. The traditional model, fixed quotas for equities, bonds, real estate, each measured against its own benchmark, made sense in simpler times. Today, with private markets, complex derivatives, and multiple objectives, it creates silos that obscure true risk and opportunity.

Her proposed Total Portfolio Approach shifts focus from individual asset classes to overall portfolio goals. Instead of asking “did we beat the Swiss bond index”, trustees ask “are we on track to meet our liabilities?” This frees managers to pursue returns wherever they find them, unconstrained by arbitrary allocation bands.

Early adopters show promising results. Funds using this approach consistently outperform over time, according to Tischendorf’s research. The challenge is cultural: trustees fear losing control, and measuring success without traditional benchmarks feels uncomfortable.

The Transfer Trap

The system compounds its rigidity with bureaucratic lock-in. When you change jobs, your new employer’s pension fund is supposed to track down and absorb your old Freizügigkeitsleistung. In practice, many workers end up with multiple dormant accounts. The government has considered forcing transfers automatically because so many people lose track of their money entirely.

This fragmentation hurts returns. Small, orphaned accounts often languish in expensive, poorly performing default options. The BVG Auffangstiftung, where money goes when no active fund claims it, has become a graveyard for forgotten retirement savings.

A Modest Proposal: Age-Based Auto-Choice

What if Swiss pension funds adopted a simple age-based glide path? Younger workers under 40 could opt for 80-90% equity exposure. Those 40-55 might hold 60-70%. Only workers over 55 would shift to the current conservative mix. The default would be aggressive for youth, with an easy opt-out for the risk-averse.

This isn’t radical. It’s how target-date funds work in the US and UK. The technology exists. The legal framework could accommodate it. The only missing ingredient is political will.

Critics will cite 2022’s market crash, when pension funds lost billions. But that’s precisely the point. Young workers who saw their pillar 2a accounts drop 15% in 2022 would have recovered and then some by 2025. The long-term trend rewards those who stay invested. The current system protects trustees at the expense of generations who never get to choose their own risk level.

The Bottom Line

Swiss pension funds aren’t failing. They’re delivering exactly what the system is designed to produce: steady, unspectacular returns with minimal volatility. The problem is that the design serves yesterday’s retirees, not tomorrow’s.

The 5.3% return in 2025 beat expectations. But when gold delivered 40%, Swiss equities 17%, and global tech even more, settling for 5% feels like leaving money on the table. For a CHF 1 trillion system, every percentage point of foregone return equals CHF 10 billion in lost wealth creation.

Giving employees investment choice isn’t about gambling retirement savings on meme stocks. It’s about recognizing that a 30-year-old’s financial needs differ fundamentally from a 60-year-old’s. The BVG system mastered solidarity across income levels. Now it needs to master personalization across life stages.

Until then, savvy young workers will keep doing what that Reddit investor did: parking their pension in high-equity strategies during career breaks, gaming the transfer rules, and treating the mandatory system as a necessary evil rather than a wealth-building tool. The system works, but not for them.

The debate isn’t whether Swiss pension funds should take more risk. It’s whether employees should have the right to choose their own risk level. In a country that prizes individual responsibility in every other domain, denying that choice feels increasingly anachronistic. The markets have evolved. The workforce has changed. It’s time for the pension system to catch up.